In our third and final instalment of the summer “Sports and Economics” series, we are turning our attention to a sport which is beloved by many in Luxembourg, road cycling. In fact, four Tour de France winners have hailed from Luxembourg: François Faber (1909), Nicolas Frantz (1927 et 1928), Charly Gaul (1958) and more recently, Andy Schleck in 2010.

When we think of the Tour de France, many of us automatically conjure up an image of a cyclist riding triumphantly through the finish line, his arms spread wide in victory. We remember the names of the overall “GC” (General Classification) winners, but rarely are we able to recall their teammates’ monikers. So – just how important is the team in helping the leader over the finish line?

The Tour de France: an ideal natural experiment

Professor of Economics at the University of Luxembourg, Arnaud Dupuy, along with co-author Bertrand Candelon (UCLouvain), had the idea to use data from past editions of the Tour de France to build a theoretical model and test their predictions about the relationship between hierarchical organisation and performance inequality within and between organisations. They asked questions such as, how do teams form when abilities differ? And, how efficient are these teams? Are all leaders the best performers?

This famous road cycling race provided the researchers with an ideal natural experiment due to a few unique characteristics. Firstly, the re-introduction of commercially sponsored teams at the end of the 60s and significant increases in prize money for the overall winner in the 1970s and 1980s offered a clear change in the incentive for riders to organise into hierarchical teams. Secondly, the fixed number of teammates. Thirdly, the availability of a direct measure of individual performance during the race (riders’ velocity) and finally, the availability of individual performance data from the Tour de France prologue, which allowed researchers to compare riders’ performance in a team setting to their performance in an individual setting and measure the differences.

After constructing their theoretical model and testing out their predications on available data from past Tours de France, researchers concluded that within teams the better riders are leaders, better leaders are matched with better helpers, and stratification is such that some helpers are more capable than some leaders (of other less able helpers). On average, 46% of performance inequality between teams in the Tour de France can be explained by the hierarchical organization within team whereas only 6% is explained by the composition of riders within team. This means that the effect of the team working together efficiently is significantly stronger than the effect of the abilities of individual team members.

A boost that can only be explained by teamwork

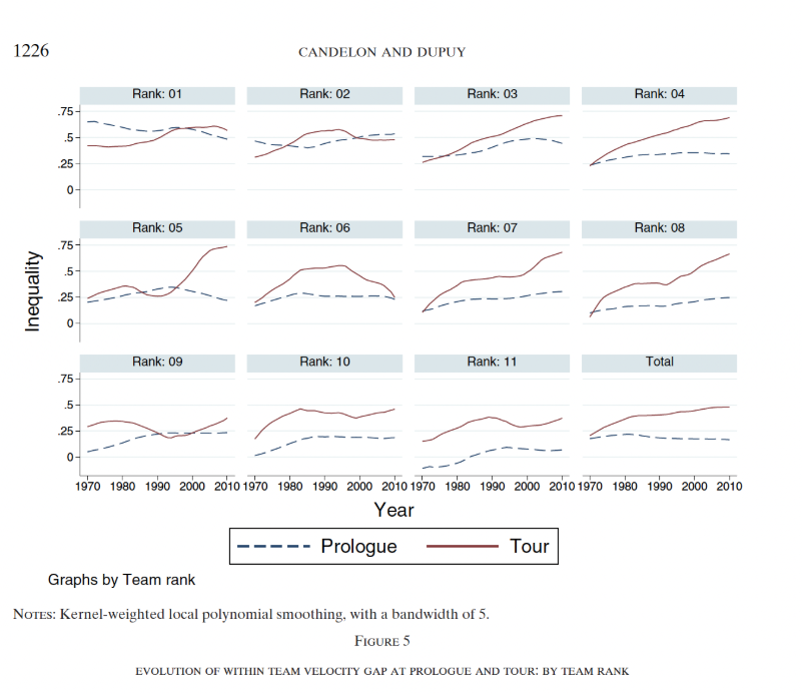

The figure below demonstrates how despite a rather flat ability gap during the prologue (where riders ride alone), the ability gap during the Tour has grown for teams of all ranks after the second-ranked team. This insight allows the researchers to separate the effects any technical changes such as doping or new technology, which would be evident in individual performance, from organisational improvements that help only team performance.

Team tactics may include drafting – following as closely as possible the slipstream of the rider in front, which can save as much as 40% of energy used compared to riding alone. Some teams designate a leader and have the remaining riders serve as a ‘wind shield’ for their leader to spare energy until critical moments of the race (final climb during a mountain stage, for instance). Teammates may also carry food and water to their leader or exchange their wheels or even bike if the leader experiences a mechanical problem during the race.

Beyond the peloton

While the theoretical model as presented in the paper is highly dependent on characteristics inherent to the Tour de France (limited number of teammates, single event, leader-helper dichotomy), the application of the research is not limited to this sport or this race. Hierarchical teams form naturally in other industries such as law practices, architectural firms, music bands and fashion houses, as workers dedicate their time (in exchange for compensation) to helping improve the output of a more forward-facing and often skilled leader.

As we conclude our Sports and Economics series, it’s easy to see now how these two fields can intersect, providing a rich playing field for economists and econometricians to build and test economic theories. Whether researchers use sports as a proxy for a socio-economic phenomenon or they apply the tools of economics to uncover novel findings about gameplay, sports and economics make a perfect team.

The original paper, Hierarchical organization and performance inequality: evidence from professional cycling appeared in the International Economic Review, Volume 56, Issue 4 (2015).