Six lessons from the field. An 18-month postdoc journey through participatory practices.

I joined the Luxembourg Center for Contemporary and Digital History (C²DH) in September 2023, as a postdoctoral researcher in Public History, Co-production and Participatory Practices. I was one of the team members working on the project “Public History as a New Citizen Science of the Past (PHACS)”. Alongside prof. Thomas Cauvin (PI of PHACS and head of the Public History axis at the C²DH), my role was focused on co-creating public history projects in Esch sur Alzette, Luxembourg’s second largest city. Having acquired a PhD in Arts and Sciences of Art, I knew that my approach to Public History would be more oriented towards artistic research and experimenting with engagement, co-creation and dissemination through arts.

Following the end of my postdoc in March 2025, I wrote this series of observations and lessons that I learned while implementing and experimenting with my research and projects. It also includes some feedback on what could’ve been done differently, sort of how to avoid this in the future. I hope it is useful to anyone trying to work along the same lines, and for those interested in getting involved, or investing in our ongoing efforts and future projects, you’ll see in my last post (lesson 6) more details about that, so feel free to get in touch!

Lessons learned

My main concern in doing the project Lovó was to find ways to include a variety of categories of participants in the work we’re doing, both in terms of research as well as in the final artistic output. The most obvious was the involvement of grandmothers in Esch. Portuguese, Cap Verdeans but also generally speaking other migrant grandmothers, in the process of selection of artworks, or in the discussion with the artists during their creation process and their residency here in Luxembourg. I had stumbled upon a wonderful initiative called Mamie et Moi which brings together grandmothers to knit and teach knitting to anyone who shows up at the different spots in Luxembourg throughout the year, as per their schedule and the founders were really enthusiastic and willing to help out but I had very little time to coordinate such a step and adding it to our already crazy schedule was not going to work out so I ended up not investing in this step.

Prof. Cauvin and I explaining our grandma stories to the participating students from the University of Luxembourg, as an intro to the collage exercise that we asked them to do to represent their own grandmas, 2024.

The other best scenario category was to involve the grandchildren of migrant descent in the work we’re doing, and along with the student assistant of our project at that time, Tatiana Martins Da Costa we tried to activate our Facebook group and even created a dedicated Instagram account for Lovó to try and get the younger generation to participate and share their grandmothers’ stories with us, but I’ll have to admit we needed a full time employee for that alone, and perhaps even some more investment in budget to try and get the word out publicly on the work we’re trying to do. Another lesson learned, experiment with the online engagement but try and make it more of a campaign with partner institutions (probably schools would’ve been the perfect ally in our case).

That being said, we still managed to do some initiatives related to the process of co-creation. For instance, we included the students at the University of Luxembourg in the process of drafting the interview questions (with an event near campus in March 2024).We also invited the participating grandmothers to a closing event at the University where we presented the outcome to them and thanked them for their involvement. The project continues to live its own life even after we concluded the tours and stopped communicating about it. We were recently invited to present it at the Centre de Documentation sur les Migrations Humaines (CDMH) in Dudelange, as a way to celebrate International Women’s Day and we invited one of the participating grandmothers Augusta to talk about her experience as a participant, but also to sing! This is to say that the project’s life and impact continue after your funding ends, or even after your postdoc ends. Find ways to make it last, maybe then you’ll have the time to involve more people, to think of more collaborative opportunities and more participation.

Grandma Augusta singing during the event organized by CDHM in Dudelange, photo courtesy of Radio Dudelange, 2025

Snapshot of the animation video illustrating the life of Grandma Elizabeth, courtesy of Romy Matar, 2025

As the project continues to evolve, I am currently putting together a documentary about the process of doing a Public History project on migration with grandmothers, which will include short animation videos illustrating each of these grandmothers’ stories, made by animation artists Romy Matar and Kareem Soltan.

While the project Lovó was successfully planned, organized and implemented, the second, led with Syrian nationals currently on their asylum seeking/refugee journey in Luxembourg and based in Esch sur Alzette, had to stop at some point during my postdoc, for several reasons mainly related to the participants’ concerns over their security and status. This might be one of the biggest lessons that I learned when doing a project that deals with such a sensitive topic. I learned to adjust my proposal depending on the situation. I learned to always put the participants’ first and to never undermine their safety, security and concerns.

The theater group during one of our public presentations in Esch, 2024.

Also, I learned to take my time to build a relationship. This might be more of an obvious lesson to learn, or maybe more of a cliché one that every researcher working with people always says. But I’m not saying take your time to build trust. I feel like using the wording of take your time and building trust shouldn’t go together. It makes it seem like it’s part of a plan to earn somebody’s trust and this is where it starts feeling like it’s an evil plan that you’re aware of but that your counterpart isn’t. When working on “Ya Bayti” (the question of home for young Syrian men currently on their asylum seeking/refugee journey), prof. Cauvin and I had discussed at the beginning of my appointment my proposal in details, along with a tentative timeline, the dos and don’ts, the safety measures, the mental health follow up, the plan to the interviews, the ethical committee review process at the University of Luxembourg and everything that goes with it. But we were also very much aware that my involvement in this project might change over time, and I was lucky to have enough flexibility to circle back on it at some point and say it’s best not to move forward with a public presentation of the outcome. Or to say that my -now- colleagues in the theater play don’t want to record an interview for a project led by their host country’s state University (that is the University of Luxembourg where I was working and where our project was based).

Community engagement means involving people in the process of creation of the work but also presenting your work to them. And in the past 18 months, I presented my work in numerous public history events, including lectures, panel discussions, conferences, informal discussions, concerts, open mics, exhibitions and even walking tours! Each of these events helped us attract diverse audiences and fostered meaningful conversations about history and its relevance to contemporary issues such as migration and the quest for home. And while some of these didn’t materialize into new partnerships, new contacts, links and ties to other similar projects or new funding opportunities, I still learned from each and every engagement opportunity. I learned about my work, how it speaks to people differently and depending on my storytelling line and depending on who my public is.

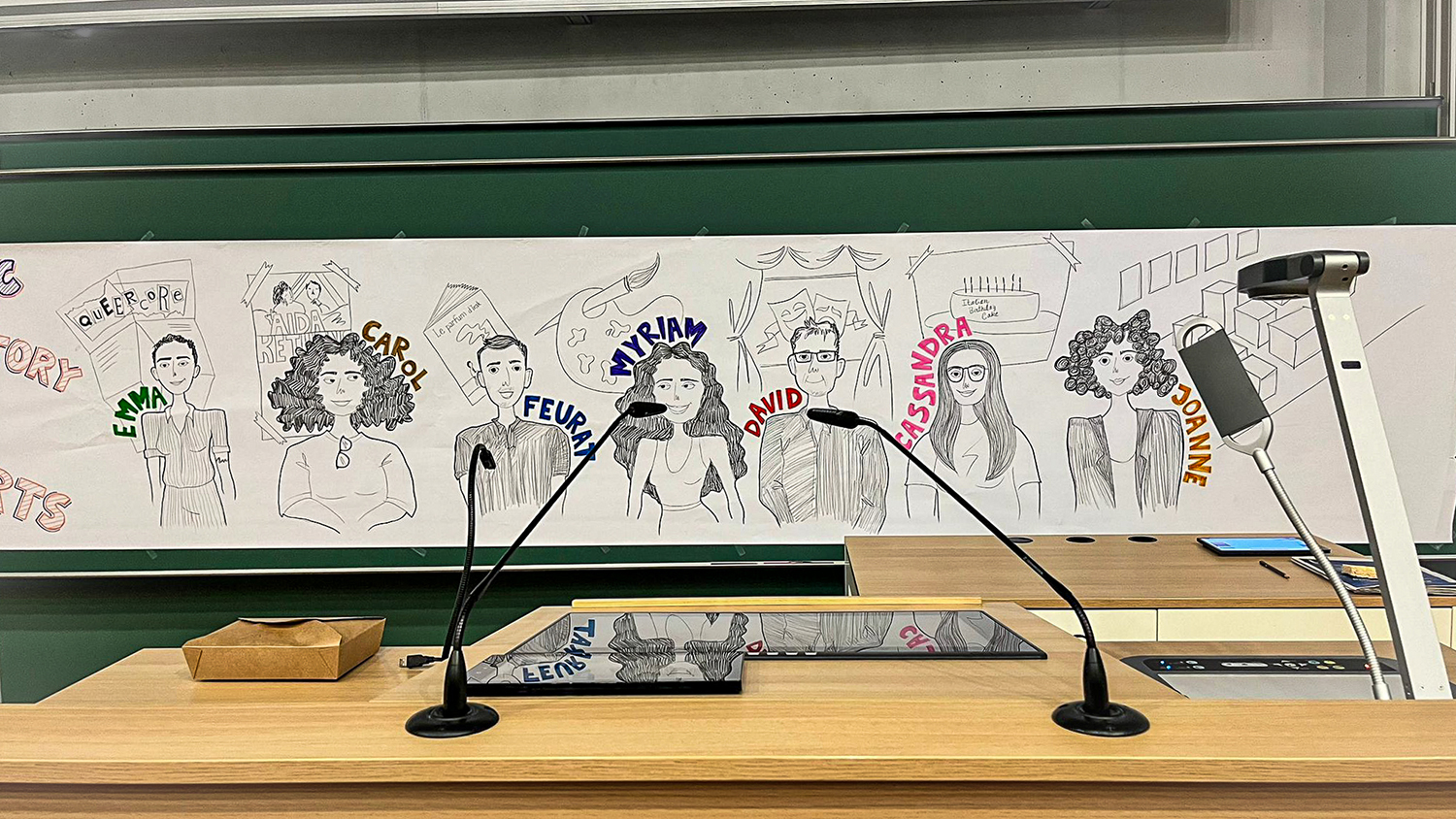

Part of the live illustration of the panel I co-moderated with prof. David Dean on Public History and Arts during the opening of the International Federation of Public History conference, which was held in September 2024 at the University of Luxembourg, illustration done by Margaux Soulacroup, 2024.

For instance, in November 2023, I participated in a talk with the University of Luxembourg’s students on migration and arts, and this is where I learned that the students feel like there’s no space for them to be critical and politically vocal. In December 2023, I presented my animation/storytelling piece “Waltz of the Displaced” in an online exhibition, which then led to my participation in a collective exhibition and conference on belonging and ways to think about displacement through art in Nicosia, Cyprus in March 2024. In December 2023, I presented my proposal for the postdoc for the first time at the Europast research colloquium (details here). This was the opportunity for me to see how early career researchers in history majors look at a proposal that’s mostly focused on artistic research. I then felt more comfortable to further invest in my storytelling ways of presenting and breaking the usual academic way of talking about our research! From June 2024 onwards (I’m sparing you the details), it became rather clear what I want my profile to address and how I want to present my previous, current and future research: I wanted to be known as the person who uses public history and artistic research to document absence and silence in political violence settings. And whether during a roundtable at Queen’s University Belfast, conference, UK (details here), or a podcast interview as part of KaleidHERscope series (accessible here), and after more than 14 events and opportunities to publicly present my research and art, I was able to test my materials and adjust my work and my approach based on people’s feedback.

While working on migration and the question of finding home, I was also grappling with how restrictive we might be in our understanding of archives, history and the past. Certain cultures, groups and communities use sound/music/silence to speak on their past and to document it. This is why I expanded my project’s scope to fit a component linking between sound and history. And thanks to the funding that I received from the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR) in June 2024, I was able to expand my research and outreach efforts. This financial support has been instrumental in the success of our projects, allowing us to carry out several activities and programs, such as the Lovó project and the “Humming Home” series, which encompassed a concert and discussion in January 2025 with artist, composer and musician Mohamed Najem (details here) and a discussion with sound artist, private ear and researcher Dr. Lawrence Abu Hamdan in February (details here).

The University is a colonial space almost by default, and working at a European University can bring so many of these “ways of doing” that should not be taken for granted. Public History and Artistic Research are both practices that embrace the multi-interpretative nature of both research, community led academic inquiry and non-hegemonic nonhierarchical structures of knowledge production. Once you realize that, find ways to make it heard.

“We Have Been Practicing Public History for Decades; We Just Didn’t Call it that Way”.

Full house during our event at Konschthal art space in Esch sur Alzette with artist Mohamed Najem and his band.

Additionally, and together with prof. Cauvin, I have also engaged in research and projects in the field of public history on an international level. Our efforts have encompassed diverse regions, cultures, and historical contexts, aiming to extend the University’s outreach and scholarly work beyond Europe on the one hand, and putting more effort in making public and community led engagement more central to our academic scholarship in public history. More specifically in the Arab world, I recently initiated 2 partnership agreements with NYU Abu Dhabi in the UAE (Al Mawrid Center) and Northwestern University in Qatar (Institute for Advanced Study in the Global South), and with both partners, we are currently implementing several initiatives such as joint conferences, faculty hosting, activating a fellowship program etc.

I have also invited several scholars/academics and practitioners from the Arab world to present their work at the Center and engage in discussions on their practices as we tried to enrich our knowledge of Public History practices outside of Europe. Using the University’s pre-existing programs and opportunities, I invited Dr. Adila Laïdi-Hanieh (Palestine) to be one of the Public Historians in residence for 2024 in April and May . I also programmed and co-moderated (along with prof. David Dean) the inaugural roundtable of the International Federation for Public History conference in September 2024. To speak about Public History and Arts internationally, I invited Feurat Alani (Iraq/France), Carol Mansour (Palestine/Lebanon), Dr. Joanne Choueiri (Lebanon/Australia). Additionally, and as part of the 1st International Public History Seminar, I invited Prof. Salwa Mikdadi to present Al Mawrid center’s work as a guest speaker in November 2024. (her presentation can be found here).

Separate from these preexisting programs, we also had the opportunity to suggest new programs, such as the Global South Fellowship for the Public History axis, which I had the pleasure to co-lead last year alongside my colleague Natália Martins. In October 2024, we welcomed Mina Ibrahim (from Egypt), Eko Saputra (from Indonesia) in November and Nayansaku Mufwankolo (from Switzerland) in December. And with colleagues prof. Frédéric Clavert, prof. Gerben Zaagsma and prof. Benoît Majerus, we activated the Scholars at risk fellowship for the C²DH in February 2025 (details here and the chosen fellow will join the Center in Summer 2025).

If you want your work to have a tangible and long-lasting impact, find ways to transfer your knowledge. Teach a course if you can, propose a workshop, a seminar, a series of events. And don’t shy away from conflict (We practically made it into a course)!

Screenshot from the CfP launched by students in the MADiPH program

Alongside prof. Cauvin, I have also drafted a new course for the master in digital and public history (MADiPH) program that could address and build on my efforts of speaking about Public History outside of the Eurocentric approach. The course “Public History in (Difficult) Global Perspectives: Dealing with Harmful Conflicting Narratives” will allow students to learn through examples how to situate public history projects and evaluate their consequences on people, communities, institutions, and broader public understanding of the past.

Coming from a not so positive person, this says a lot. But I trust my capabilities, I am aware of what opportunities I have and how I could utilize what I have learned thus far to change, to confront and to make it work a bit better, and I know that I’m not a quitter. My postdoctoral fellowship ended early March, but the PHACS project duration has been extended for a full year (till May 2026) and for that, prof. Cauvin and I will continue working to build our international partnerships and networks in Public History in and beyond Luxembourg. As the partnerships manager for PHACS, I look forward to continuing our efforts and building on our successes, with a first stop in Cairo, Egypt, working alongside Shubra’s archive to experiment with community archiving practices in different contexts and cultural landscapes. You can stay up to date with our latest partnerships and initiatives beyond Europe here.

View from Shubra’s Street, 2012, Courtesy of Dr. Faris El Gwely, Wiki commons

Context: Exile and the Question of Finding Home as a Public History Inquiry

Working on the history of migration and the question of finding home in Esch-sur-Alzette was my main project during my appointment. I created and co-led two sub projects: One focused on Portuguese speaking grandmothers of Esch sur Alzette (Lovó), and the other (Ya Bayti) with Syrian nationals currently on their asylum seeking/refugee journey.

AI generated illustration of one of the stories of Grandma Adriana who saw snow for the first time in her life the day she arrived to Esch sur Alzette in April 1972, Generate through Co-Pilot AI, Myriam Dalal, 2025.

The project Lovó included six oral history interviews with the grandmothers, capturing the personal stories and experiences of individuals from various backgrounds. These oral histories have been preserved and presented to the public in September through audiovisual tours including light installations in Esch made by artists Duarte Perry, Marieke Leene and myself, as part of a partnership with the 1st Cultural Biennial of the city of Esch. The richness of these narratives has added depth and context to our understanding of historical events, allowing us to appreciate the human experiences behind them. The interviews and their transcripts will be made available soon through the platform HistorEsch Geisinn.

Author(s)

Myriam Dalal

Lessons learned

- Lesson 1 Participation doesn’t grow on trees

- Lesson 2 Voicing displacement experiences can and will get political

- Lesson 3 What happens in Luxembourg should not stay in Luxembourg

- Lesson 4 History making tends to overlook non-Western practices of making history: Find ways to break that cycle

- Lesson 5 Teach what you practice

- Lesson 6 The best is yet to come