Research scientist and migration scholar Inna Ganschow’s publication on forced labourers from the Soviet Union in Luxembourg during World War II was released early this month. It’s just one of the many ways she is raising voices for individuals in overlooked communities.

A prolific writer, Inna Ganschow says that for every project she’s working on, she has more in the pipeline. “I’m a storyteller,” she explains. “I like people. I like migrants. I like women. Underprivileged people deserve a voice.”

With broad interests across various disciplines—oral history, the language heritage of minorities, writing techniques in captivity—plus a solid background in journalism, she has several books to her name, including her PhD thesis in 2013 on postmodern Russian literature and a monograph on multicultural migration from Russia, titled 100 Jahre Russen in Luxemburg. Geschichte einer atomisierten Diaspora in Luxemburg (100 Years of Russians in Luxembourg: History of an Atomized Diaspora) published in 2020 in German.

Over the past few years, her research at the C²DH has predominantly focused on two main areas: research on the history of Soviet forced labourers in Luxembourg during World War II for her latest publication as well as recording and analysing the oral histories of recent Ukrainian refugees following Russia’s invasion of the country in 2022, captured in Witnessing the Now and the subsequent U-CORE project. Despite decades separating these two distinct chapters in history, these projects have intersected in unexpected, yet significant, ways.

Recording oral histories of recent Ukrainian refugees

One door closes, another opens

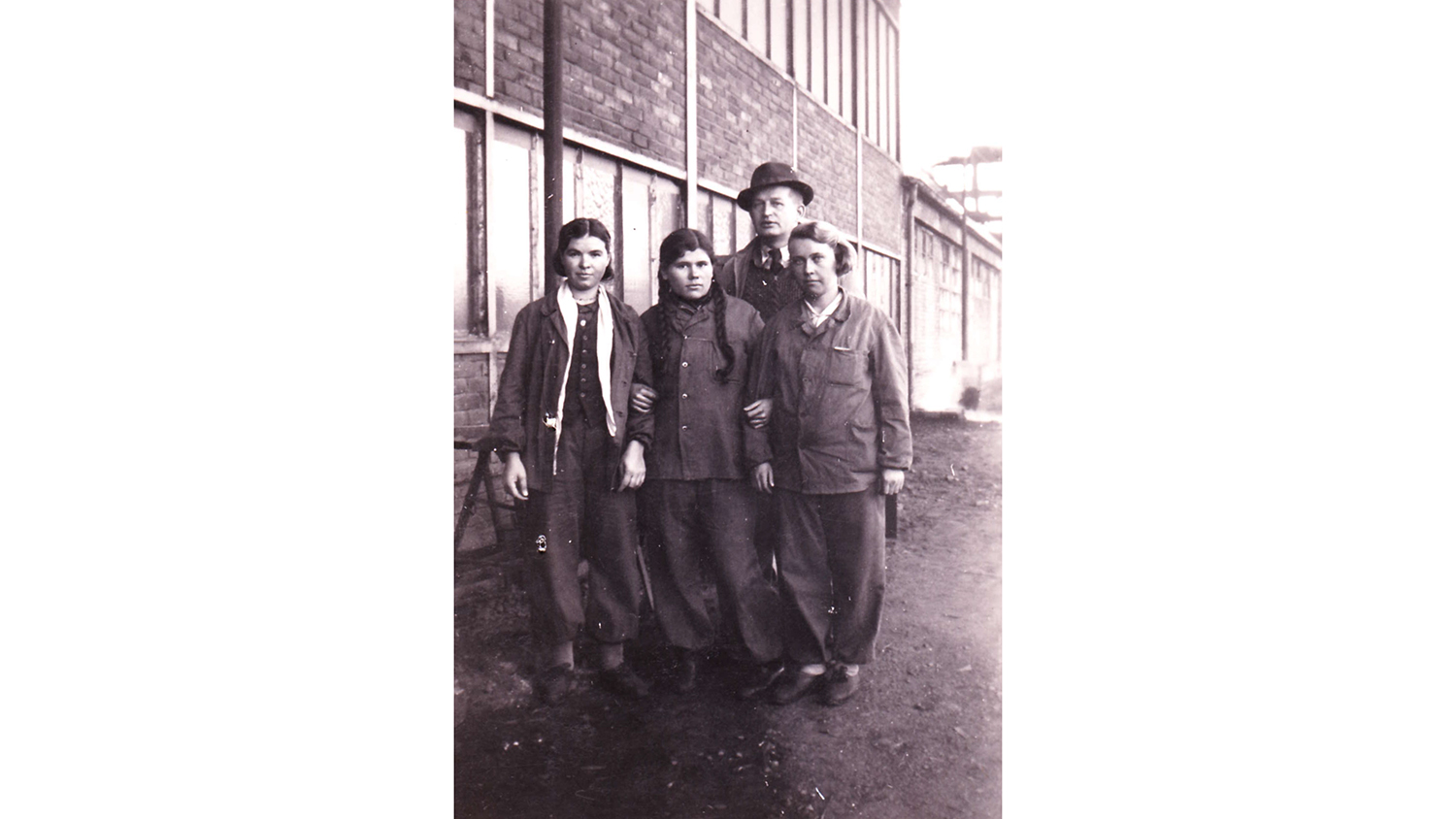

Ganschow worked on her latest publication, “Keiner weinte, es gab keine Tränen mehr”. Ukrainische, russische und belarussische ZwangsarbeiterInnen in Luxemburg im Zweiten Weltkrieg aus transnationaler Sicht“ (Nobody Cried Anymore: Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian forced labourers in Luxembourg during the Second World War in transnational view), in 2021-2024. The research on Soviet forced labourers in Luxembourg, financed in cooperation between the Luxembourg Ministry of State and the C²DH, is the first academic project on this topic. It aims not only to approach the topic in the transnational view, but also to glean more insight on the personal histories of those brought to work in the steel mills of Luxembourg, one of which was situated at Belval, Esch-sur-Alzette, where the University of Luxembourg today has one of its main campuses. Forced labour in the Grand Duchy is moved from the level of the local episode into the context of European and world history. “This is the history of Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian civilians—mostly females, mostly teenagers, mostly dealing with male administration in three different types of camps: German, American and Soviet,” Ganschow explains, adding that male prisoners of war also served as forced labourers not only in the steel industry but also in the agricultural sector and private households.

“Keiner weinte, es gab keine Tränen mehr”. Ukrainische, russische und belarussische ZwangsarbeiterInnen in Luxemburg im Zweiten Weltkrieg aus transnationaler Sicht“ book launch with Inna Ganschow

Initially, her intent was to travel to Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus for archival research and get accounts of eyewitnesses or their descendants, but these plans came to a halt with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Ganschow turned to American archives instead, which provided her with a wealth of information.

Meanwhile, Ganschow began learning Ukrainian and volunteering with MMS Humanitas e.V., an ad-hoc organisation from Birburg, helping 800 people at the Ukraine-Poland border be placed into 300 German families near Luxembourg’s borders. Being in contact with these refugees opened another new door for her research: some were willing to be interviewed for Witnessing the Now and U-CORE, others were Ukrainian researchers. Ganschow therefore helped found the Luxembourg Ukrainian Research Network, or LURN, and her Ukrainian counterparts provided her with critical connections. “The war closed certain possibilities for me but opened other ones, through the new language, new colleagues, a new network,” Ganschow recalls.

Memories of life as a labourer, and beyond

Although some of the local archivists in Ukraine were able to provide Ganschow with materials, there were, of course, other challenges. Archivists were working under horrible circumstances, including bombing, with heating, electricity and internet connections often down. If it hadn’t been for the war, Ganschow might have had to visit each of the local archives, given that they require individual labourer names for conducting research. “Still, despite this emergency, people were interested in the history and willing to help,” she says. “Exactly where the war is happening now, most of the refugees coming to Luxembourg were coming from these regions also 80 years ago. Those were pretty much the same regions where the first labourers were brought to Luxembourg.”

Once regions fell under Russian occupation after the 2022 invasion, Russian archival laws were imposed. This meant that personal dossiers could only be accessed by relatives, thereby preventing Ganschow from any access.

Ostarbeiterinnen bei der ARBED, vermutlich vor dem Gebäude der „Möllerei“ in Belval (Familienarchiv Ritzerow).

Although Ganschow didn’t find any witnesses still alive, she did find some of their relatives, some of which were able to provide her with photographs and other so-called “ego-documents”. She was also given a 35-page notebook created by one of the forced labourers, Maria Talpa. “She wrote how she remembered her time in Luxembourg, starting with her childhood which is very important,” Ganschow says. The account reveals more about Holodomor, a manmade famine in Soviet Ukraine in 1932-3; the death of Talpa’s siblings; mistreatment in Luxembourg and later by the Soviets.

This account is, unfortunately, not unique: even upon their liberation from the NS-camps, forced labourers were not free and were moved to American Displaced Persons (DP) camps. Before the return to their home regions, these victims were interrogated again, this time by the Soviets in their filtration camps in the Soviet-occupied areas of Germany, and then again at home. For women, whose male peers of the same age were often killed in war, it wasn’t as easy to start a family with their younger counterparts, so some remained single. But some came back home with the husbands they met in Luxembourg during their forced labour.

In addition to sharing these stories and research through her publication, Ganschow is hoping to get the broader public more interested in this part of Luxembourg’s history, even if it’s a bit “inconvenient”. “We think a lot about how memory works and how commemorational jobs should be done—as a physical monument? As a permanent or temporary exhibition? As a website with names and biographies?” she adds. “That’s why the C²DH is great: they’re providing the means and the tools for digital humanities, making the contribution to all formats possible.”