The students are not the first to come to Campus Belval every day. Eighty years ago, it was young people who had been deported from the occupied territories of the USSR to Luxembourg to work in the steel industry in Belval.

Today, there is no trace of the presence of the Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian girls who were forced to work for ARBED in Belval every day. One of their barracks camps was right next to the factory, where the roundabout is today at Raemerich. The male camp for male Soviet prisoners of war was located between the current Lyceum Bel-Val and the two chimneys. There were several such camps throughout the country: in Schifflange, Lallange, Esch, Dudelange, Differdange… In total, about 4,000 people, mostly young women from Ukraine, were found in the course of the scientific project conducted in six countries, 2,600 of whom were identified by name.

Female barracks camps near the Raemerich roundabout

The male camp for Soviet prisoners of war was located between the current Lyceum Bel-Val and the two chimneys

When Inna Ganschow research project about the forced Soviet laborers in Luxembourg began in 2021, not only archive research was planned, but also film trips to Ukraine, Russia and Belarus, where the descendants of the former forced laborers had to be interviewed. It was to be a larger-scale documentary project, realized using the methods of oral history and the tools of digital humanities, with text and moving images, multimedia and comprehensible for both scholars and interested lay readers. But the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 put a stop to the travel plans. Neither the archives nor the descendants could be contacted and visited.

Remote research and interviews

However, this project was realized – on the one hand through the use of technology, and on the other hand through the commitment of people who helped to find the documents and eyewitness testimonies on both sides of the borders and sometimes the ocean. Above all, the Ukrainian scholars who came to Luxembourg as refugees put Ganschow in touch with the archives and other researchers who, under fire and often without electricity or internet, tried to make the documents accessible to her. On the other hand, the American archive NARA, which stores the documents of the American army that liberated Luxembourg in September 1944, provided important insights.

Life of a forced laborer

We now know, for example, that the lives of Soviet youth who had been abducted by the Germans to occupied Luxembourg had a difficult childhood. Because most of them came from Ukraine, they survived the great famine called Holodomor in the 1932-1933. Many were orphaned because their families did not make it. In the occupied western territories of the USSR, which since 1939 had included eastern Poland, they were exploited by the occupation army. Some were lured to Germany, the others were tricked, the third were forcibly put into the cattle cars to arrive after two weeks in Luxembourg.

Life here was full of humiliation at the hands of the civilian population, inhumane treatment by the camp and factory guards, and hard, unskilled labor underground in the mines and above ground in the factories. However, there are beautiful stories of solidarity between Luxembourgers and Soviet citizens. After the war, some married, but only a handful were allowed to stay. In an informal exchange, all of them had to return to the USSR, regardless of their desire to do so, so that the Luxembourgish forced recruits from the Wehrmacht who ended up in Soviet captivity could be released.

Not the end

One might think that this was the end for the Soviet forced laborers. Although Luxembourg was liberated by the US-Army in September 1944, they still had to remain in their camps, which were now administered by the Americans and were called DP camps. After the repatriation that had begun, in 1945 they were sent to the new camps in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany, which were called filtration camps. Even after their return to the USSR, they had to be interrogated again for espionage and collaboration. Many were not allowed to go home at all but were sent to rebuild the destroyed plants and factories. Nobody was allowed to go back to Moscow, Leningrad and Kyiv.

Those who married their fellow sufferers could count on their partner’s understanding. Otherwise, as a former forced laborer, one was often publicly shamed for having helped the enemy during the war, for having helped the enemy to produce weapons in the steelworks that had been used against their homeland. Many female Eastern workers could not marry people of the same age, because they died in the war. Almost all of them struggled with the physical and psychological consequences of forced labor in Luxembourg. Apparently, no one received compensation because no one could prove, despite their attempts in the 1990s, that they had been deployed here. With this project, names are being documented for the first time, but there is no one alive who could still benefit from compensation.

The result of this scientific project led by Dr. Inna Ganschow from 2021 to 2024 at C²DH, funded by the Luxembourg Ministry of State is the book “Keiner weinte, es gab keine Tränen mehr” (‘No one cried, there were no more tears´. Ukrainian, Belarusian and Russian Female Forced Laborers in Luxembourg during the Second World War from a Transnational Perspective) edited by the C²DH and capybarabooks.

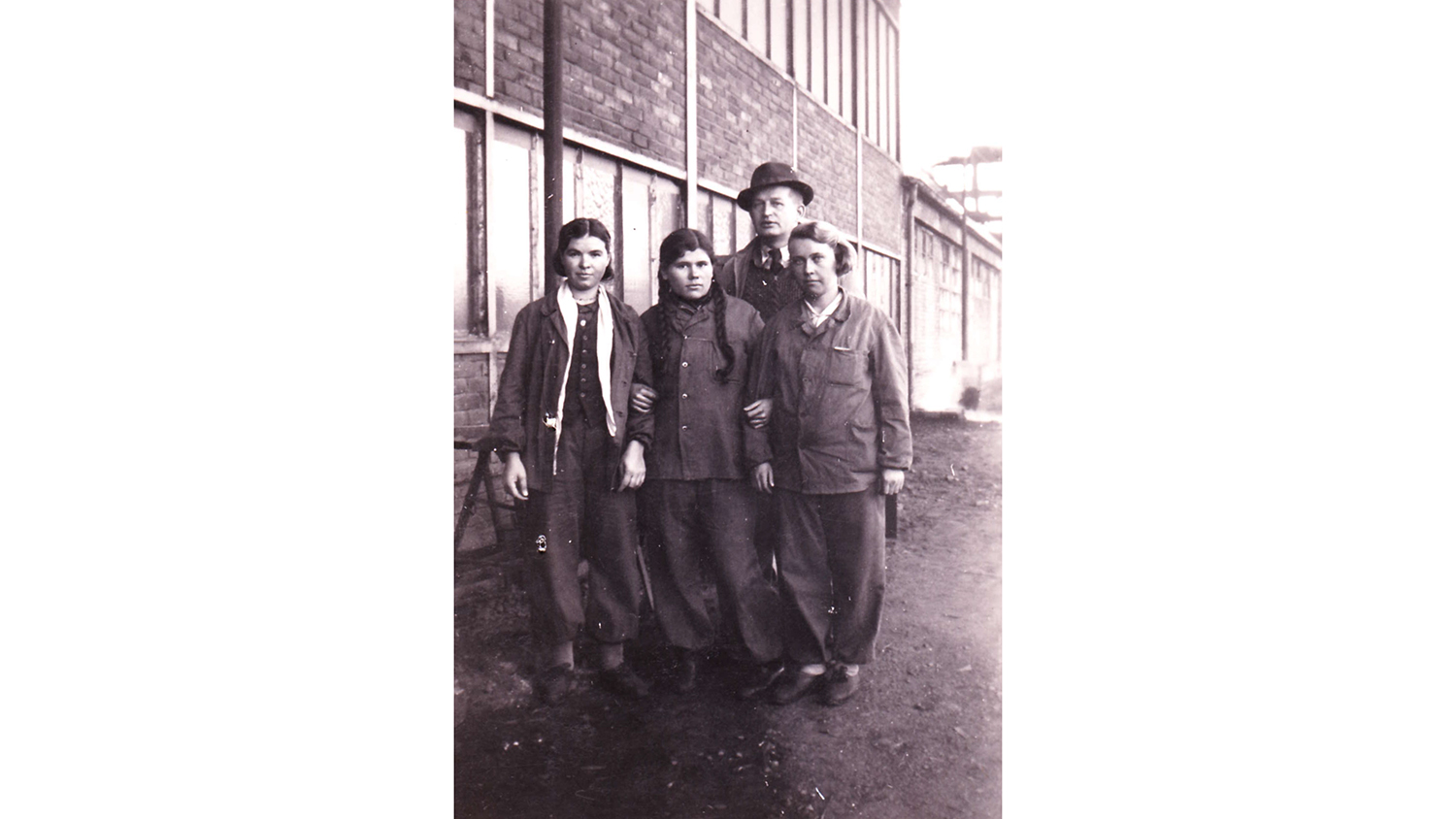

Main photo: Eastern workers in the south of Luxembourg, who were employed not only in Luxembourg industry, but also in agriculture, in private companies and in transport companies such as the Reichsbahn, 1942-1944 (Photo: Gilbert Schmit)

Meet the researcher