‟ A common misconception is that technology itself can solve problems. In reality, we need perspectives from the people affected by the systems and input from multiple fields.”

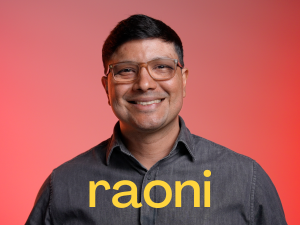

Meet Raoni de Paula Lourenco: from teaching Samba on stage in China to predicting steel quality in Luxembourg, Raoni’s journey defies convention. A Brazilian computer scientist who began coding in high school, he’s spent his career seizing unexpected opportunities – guided by a seed planted by a maths teacher when he was just 10 years old. Now at SnT, he bridges industry and academia, applying AI to manufacturing challenges while staying true to a core belief: the best way to tackle frustration is to learn from it.

Relive the conversation – transcript below!

Could you briefly introduce yourself and your academic path?

I came to Luxembourg two years ago. Before that I studied computer science for both my bachelor’s and master’s in two different public universities, one in my hometown in the Amazon rainforest and another in southeastern Brazil. Later, I completed my PhD in computer science at New York University. A seed was planted early when a maths teacher taught me a few lines of code in a language called BASIC at age 10 and since then I’ve simply followed the opportunities that appeared.

What research are you currently working on at SnT?

I work in partnership with the company Ceratizit together with their data science team and PhD students at SnT. We apply machine learning to manufacturing challenges in the steel industry, focusing on knowledge discovery, document retrieval, and explaining AI predictions. A key objective is to help the company understand why automated systems make certain decisions, including which internal or external factors influence a model’s forecasts.

What drives your research?

The first word that comes to mind when I think about my research is “why”. I’m driven by the need to understand the root causes of computational behaviour. Much of my work feels like solving the same puzzle in different ways and then identifying the patterns across those solutions.

Could you share a memorable experience from your research career?

My teenage self wouldn’t be surprised about my path, though.

‟ Once I was working on a project and went to a workshop in China where I ended up on stage teaching colleagues how to dance samba.”

What have been the biggest challenges throughout your research career?

The biggest challenge has always been learning to cope with the frustration of failed attempts. Research involves many approaches that simply don’t work. The only productive way forward is to understand whatever knowledge the failure provides and try another path.

Who inspires you in your professional journey?

Rather than having a single role model, I draw inspiration from many people, such as friends, family, teachers, and mentors. I’ve always tried to learn from everyone I encounter. My mother especially influenced my observational approach to the world.

How has your background shaped your approach to technology and problem-solving?

Being of Indigenous descent from the Global South, I always consider how a problem will impact users and society. I grew up with many interests – performing arts, sports, and math – and was lucky to begin research early in an environment that felt culturally familiar, but interacting with researchers all around the world. This helped me feel at ease in technology and taught me that there is no single “mode” of a tech researcher. Everyone’s perspective adds value.

What misconceptions about technology or tech research do you often encounter?

Another misconception is that certain research areas are gender specific. Throughout my career, I have worked with and been mentored by many women who were proving the common misconception wrong: that the best in tech are always male.

What would make tech research environments more welcoming and inclusive?

Creating an inclusive environment requires empathy for a wide range of working styles. Seeing the diversity at SnT even before joining made me feel welcome.

‟ We need to embrace differences. I enjoy communication and believe that talking and socialising help build community. But I’ve also learnt that some people contribute best without much interaction, and their work is equally valuable.”

What does tech research need more of in the future?

Tech research needs deeper collaboration with the social sciences and humanities. Communication is also an underrated skill; we often focus on technical aspects and overlook the importance of explaining our work clearly.

Supported by the Luxembourg National Research Fund