Author: Constanze Metzger

As part of the Women Leaders lecture series organised by the Gender Equality Office, I spoke with media artist Tamiko Thiel, renowned for her pioneering work in augmented reality (AR). Thiel earned a B.S. in Product Design from Stanford University in 1979 and an M.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1983, where she specialised in human-machine design and computer graphics. Her acclaimed works are featured in major museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the San Jose Museum of Art, among others.

You have a professional background in arts and technology. How do these two fields influence you?

As an undergraduate, I chose a major that combined engineering, art, and design. I studied Product Design at Stanford, technically an engineering degree but with space for art and design courses. That was my starting point in the 1970s.

After graduation, I worked as a product design engineer at Hewlett Packard in Silicon Valley, designing injection-molded parts for computer terminals. When the work became repetitive, I moved to MIT for a master’s in mechanical engineering.

After completing the required courses, I explored electives and discovered two groups in the Architecture Department that later became the MIT Media Lab – the Architecture Machine Group and the Visual Language Workshop.

I took courses in computer graphics and in art and design that explored society and culture. A Bavarian German professor encouraged us to reflect on our place in society and express it visually. That was the turning point. I called my parents and said that while I could work as an engineer, what I truly wanted was to become a media artist. That was in 1982, and it defined my path.

© Lynn Theisen – Melt Studio

“My education was rooted in physics and mechanical engineering. These were creative environments, yet I felt a void, the absence of art.”

Is there a different way of thinking as an artist compared to an engineer?

My education was rooted in physics and mechanical engineering. At MIT I was surrounded by my social crowd was people like Marvin Minsky and his students in the MIT AI Lab. After graduation one of them, Danny Hillis, asked me to join his new company Thinking Machines Corporation, where I was lead product designer on his Connection Machine – the world’s first AI supercomputer, and even worked with Nobel physicist Richard Feynman. I worked on the Connection Machine with Danny Hillis at Thinking Machines Corporation.

Tamiko Thiel, lead product designer, Connection Machine CM-1/CM-2, (1986/1987, Thinking Machines Corporation). Installation view with CM-2 at the Museum of Modern Art New York, 2017.

These were creative environments, yet I felt a void, the absence of art. My mother was an artist who moved from abstract woodblock prints to Japanese performing arts and then calligraphy. My father came to MIT in 1950 as a lecturer in naval architecture and while there shifted to design and architecture, focusing on how people move through inhabit and perceive space.

That dual background showed me what was missing in my highly technical world. When the Connection Machine project ended, I left the technology bubble. I left my job, home, and language and moved to Munich.

The Munich Academy of Fine Arts was traditional, centered on painting and sculpture, but one design professor and his assistant worked with video and even simple computer graphics. Access to video and computer graphics was rare, and that became my entry back into digital and media art.

You left a stable career to start over. Where did you find the courage?

I knew I could return to engineering. Hewlett Packard supported women engineers, and I had mentors and a strong network. At Thinking Machine I had just completed the design for a five million dollar AI supercomputer, which gave me confidence.

My father always said to do what you truly want because you will be good at it and it will work out. He had left naval engineering to become an architect. We did not have much money, but we lived among artists and designers who made it work. That gave me faith.

How does augmented reality influence memory in your art?

Augmented reality is the latest way to connect stories to places. Humans have long said to each other, do you know what happened here? AR continues that tradition and anchors memory to place within without using physical space.

History is often written by those in power. AR can reveal hidden or alternative histories. Multiple narratives can coexist in one place, similar to quantum superposition. A location can hold many intertwined and valid stories.

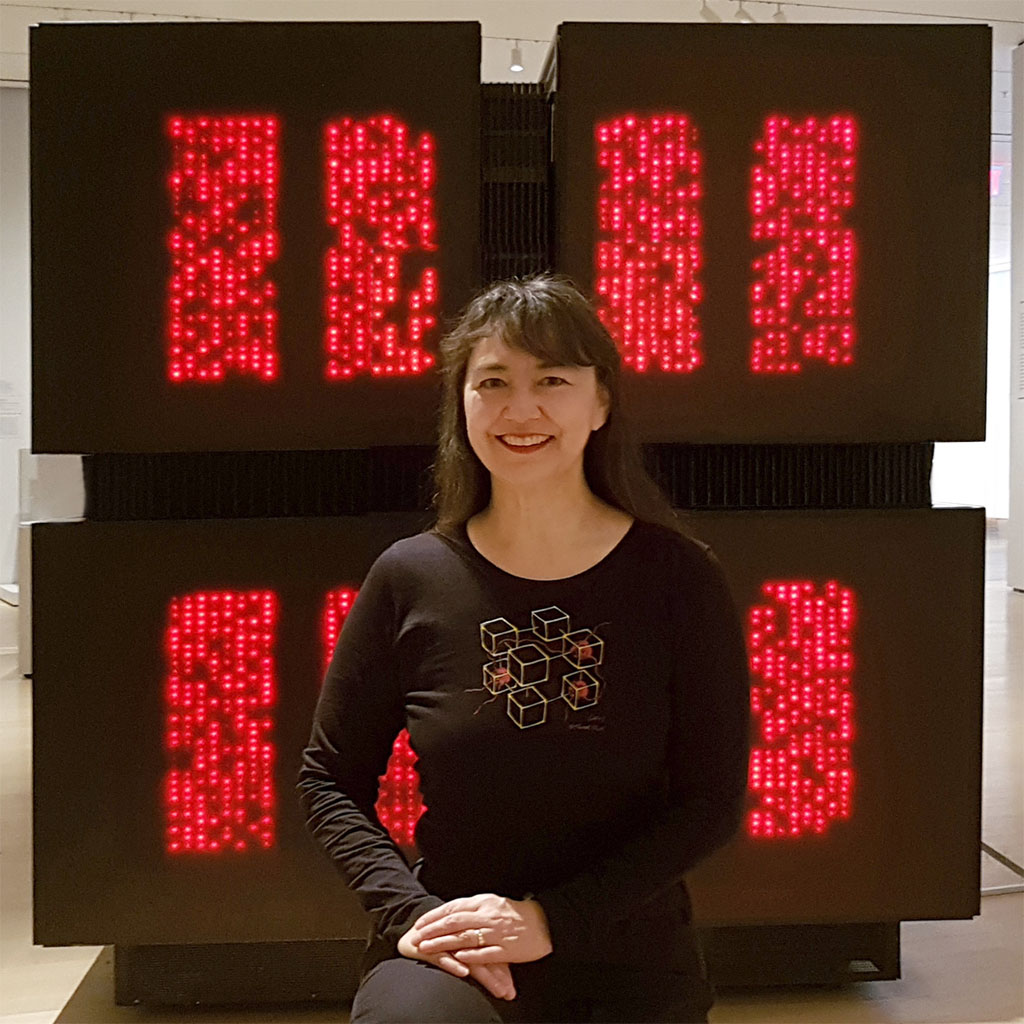

“AR offers visibility to underrepresented voices and creates space for dialogue.” Artwork: Tamiko Thiel. Photo: Lynn Theisen-Melt Studio, 2025.

So AR becomes a form of activism?

It can. AR offers visibility to underrepresented voices and creates space for dialogue. Parts of the art world still seek exclusivity, but that is changing. With basic media training many people can create AR works. It has become a democratic form.

Is there an ethical dimension when anyone can use it?

All art has an ethical dimension. Public art, physical or digital, invites debate. AR lowers permission barriers for creating in public space, which opens participation and dialogue. If we value free expression, we must also accept disagreement.

What is next for AR?

AR glasses and mixed reality headsets are advancing. Devices such as Meta Quest 3 with full color passthrough bring AR into real environments, even if still bulky.

More important is accessibility. AR will grow as a medium for creation, not only consumption. Anyone can build and share virtual works. That democratization is what excites me most.

What advice would you give to women who might take an unusual or risky path, as you did?

One piece of advice that stayed with me came from a friend who, like me, came from a modest background but studied among very wealthy classmates. She once told me, “They have trust funds behind them. They don’t have to think about whether they can take a risk.” That sentence made me realize that confidence often comes from security.

If you don’t have financial safety to fall back on, you have to build it for yourself. Find a way to cover the basics – rent, food, a bit of stability – and once you have that, you can take risks with much more freedom, just like those who were born into it.

When I was 16, after being accepted to both MIT and Stanford, I remember walking down the street thinking, “If I were to die in the next thirty seconds, I would still feel at peace because I took the opportunities life gave me.” That thought has guided me ever since. I try to live in a way that, if I were to die tomorrow, I would not regret the things I never dared to do.

I also chose not to have children, simply because it was never what I wanted. That gave me flexibility. My husband, who is a programmer, supported me at times when I needed time to focus on my work. Now that we are nearing retirement, he helps with my art projects which are finally bringing in money for both of us. But I always knew I could earn my own money. It is never just about money or stability. It is also about finding the right partner, someone who does not hold you back.

Earlier in life, I had partners who told me to choose between them and my art. I always chose art.

Tamiko Thiel with the Connection Machine CM-1 t-shirt she designed, and Richard Feynman poster from Apple’s “Think Different” campaign. San Francisco, 1998.

Photos: Lynn Theisen-Melt Studio, 2025.