In the next weeks, we propose a three-part Sports and Economics series where we present and explain sports-themed academic papers from our Department of Economics and Management researchers. We begin with Professor Arnaud Dupuy’s recent IZA discussion paper, “Who Does What to Whom in Tennis? A Threshold-Crossing Stochastic Model of Tennis Rallies.”

From Childhood curiosity to academic inquiry

When Prof. Dupuy was a young boy, he bought the French sports newspaper, L’Équipe whenever he could. But instead of hurrying to read the headlines, he flipped to the back pages of the paper where the players’ statistics and rankings are published. He liked to analyse the data that he found there. In particular, Prof. Dupuy enjoyed playing around with the numbers and calculating alternate scenarios, or what economists call ‘counterfactuals’.

Soon the time came to choose a university programme. His ease with numbers led him to study economics, but his passion for sports never went away. As Prof. Dupuy learned the econometric techniques used by economists to explain individual or organisational-level behaviour, he figured that such thinking could also be useful to help gain further insight into many different sports competitions. Furthermore, sporting events and the data that they generate can also provide economists with natural experiments to test their theories.

Now, Professor Dupuy regularly helps his students understand economics by using examples plucked from the world of sports. Throughout his research career, he has found opportunities to bring passion and profession together, such as his recent paper on tennis rallies.

A novel way to understand game play

Summer means tennis. Three out of four Grand Slam tournaments are played between May and September, with the Wimbledon final happening this week. Tennis fans are drawn in by the fast-paced exchanges, powerful serves and skilful returns. Tennis players need to employ a combination of strength, technique and restraint, to make sure that the ball remains in bounds. With each back and forth or ‘rally’ between players, the atmosphere grows more and more tense. The question of who will score the point keeps fans’ eyes glued to the game. For a casual fan, the game is pure entertainment, but for a fan who is also an economist, it is an irresistible opportunity.

Prof. Dupuy sought to understand the underlying mechanisms behind this power struggle between the two players. He wanted to answer a strategy question originally posed by ex top 5 ATP player and international coach Brad Gilbert, “Who does what to whom?”. By building a model based on techniques usually employed in the field of economics, Prof. Dupuy used publicly available data from thousands of tennis matches to reconstruct player profiles and gain insights into player styles. Instead of looking at the tennis match as a series of rallies, like other studies had done, he broke it down even further, into shots.

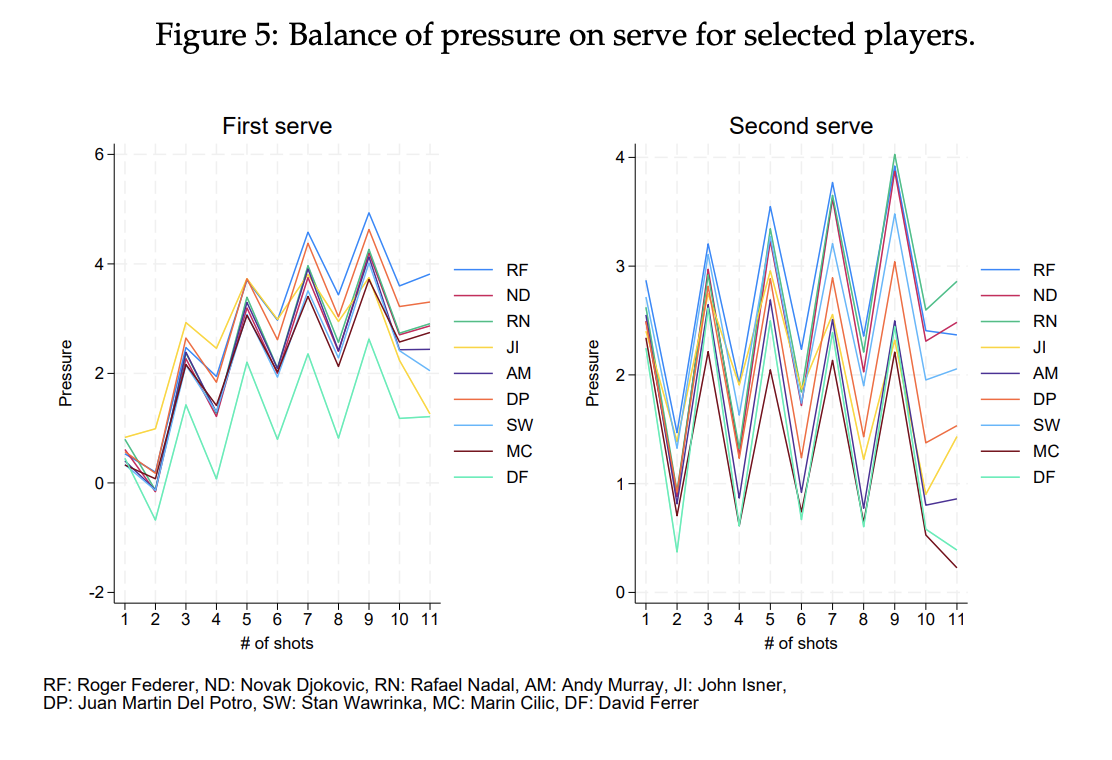

At this more granular scale, Prof. Dupuy was able to calculate the relative quality of each shot in a given rally, based on if the opponent was able to return it or not. The quality of the shot can be seen as the pressure that it exerts on the player who returns the ball. A rally continues as long as each player produces a high enough pressure on his shot for it to pass the ‘quality threshold’. Each exchange results in a cumulative pressure differential, with some players able to increase the balance of pressure as the game unfolds, while others struggle after a certain rally length. In tennis, the serving player has a distinct advantage, which makes it essential to create player profiles on the serve and on the return as well. Tennis rules also allow a player two serves, should the first one end in a fault. It is therefore necessary to compare the pressure of first serves and second serves.

(Many more graphs and examples are available in the original paper)

By comparing the pressure of each shot on and after the first and the second serve for a selection of big name tennis players (see above figure), we can see for example a distinct difference in game play between tennis greats. Raphael Nadal, for example, is the only player who, after the second serve, can increase his balance of pressure as the rally unfolds, while all others maintain the level of pressure or see it decrease. Another observation from the graph is that on the first serve, tennis legend Rodger Federer is able to increase the pressure of his shots the most in comparison to the other players.

The paper also proposes a sequence of graphs which represent specific rivalries. With the data, we can see that each of the big 3 (Federer, Nadal, Djokovic) has one player who is able to neutralise his first serve. For Roger Federer it is Rafael Nadal, for Rafael Nadal it is Novak Djokovic, Novak Djokovic it is Roger Federer.

Understanding, Not Predicting

While data scientists may use artificial intelligence and large language models to try and predict the outcomes of matches, this is not the goal of an economist like Prof. Dupuy. His interests lie in highlighting the mechanisms behind observable phenomenon, in sports or elsewhere in society.

With access to more data, such as those collected through the Hawk-Eye computer vision system, Prof. Dupuy could drill down even further and study how different kinds of shots affect pressure balance. For now, the model offers a novel perspective on tennis strategy and a compelling example of how economic thinking can illuminate the inner workings of sport.

About the researcher

Prof Arnaud DUPUY

FDEFVice-Dean of FDEF, Full professor in regional and international economics