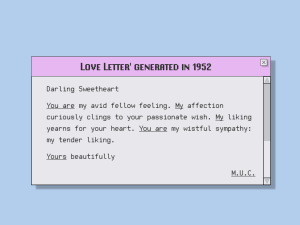

In 1952, the Ferranti Mark I, one of the world’s first computers at the University of Manchester, did something extraordinary—it generated a series of randomly assembled love letters. These were no ordinary declarations of passion; they were written entirely by an algorithm, signed by “M.U.C.” (Manchester University Computer).

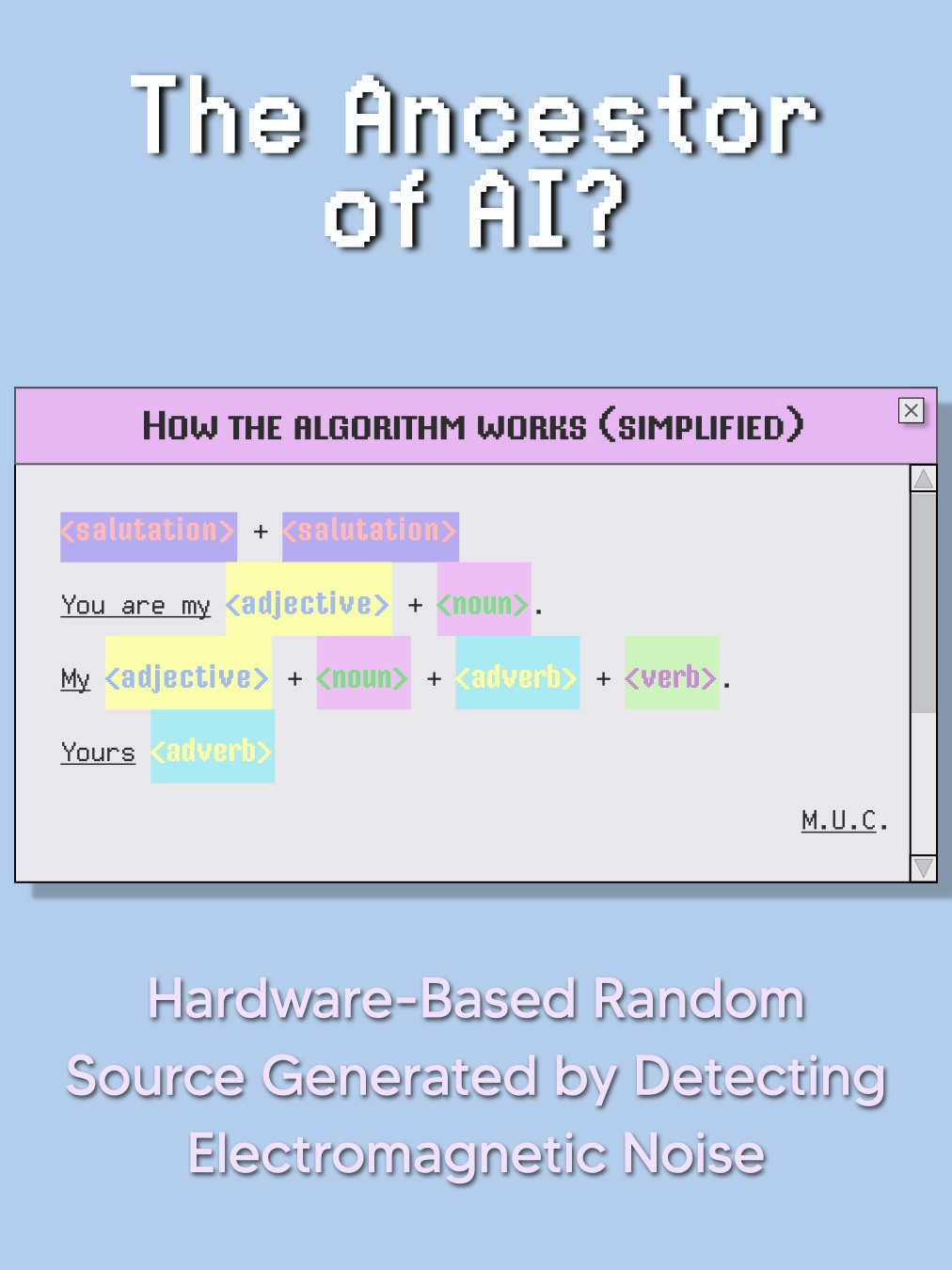

This playful algorithm, created by Christopher Strachey, wasn’t just a quirky experiment—it was a groundbreaking moment in digital creativity. Strachey’s code parodied human writing with absurd yet poetic results, using true randomness from hardware-generated noise to create unique, gender-neutral love letters. While some saw it as a mere joke, it was, in fact, one of the earliest instances of a machine mimicking human expression—a direct ancestor of modern AI.

More than a technical marvel, the program reflected its time. Strachey—who, according to his sister, struggled with his sexual identity—was a contemporary of Alan Turing, the father of AI, who faced tragic persecution for his homosexuality. In this context, Strachey’s love letter generator takes on deeper meaning. It parodied traditional love letters while subtly sidestepping societal norms, generating anonymous, machine-written messages that were free from human suspicion.

Several sources attest to the fact that Alan Turing and Christopher Strachey were both greatly amused by the results of the algorithm, unlike their colleagues at the time who, according to Turing’s biographer Andrew Hodges, were busy doing “a real men’s job” and dismissed the algorithm as childish and a waste of time. The gender-neutral, anonymous love letters could be seen as a quiet act of rebellion—a way to express affection in a society where same-sex love was criminalized.

Strachey’s code was more than a technological curiosity—it was a statement. By turning love into an algorithm, he expanded the boundaries of what computers could do, laying the groundwork for today’s AI-generated poetry, chatbots, and digital creativity. His playful experiment reminds us that technology is never just about logic—it’s about the stories, identities, and emotions embedded in the code.

Titaÿna Kauffmann, a PhD student at the Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C²DH), currently works on «code as a source» supervised by Prof. Valérie Schafer, as part of the “Deep Data Science of Digital History” (D4H) project, a new Doctoral Training Unit funded through the FNR’s PRIDE programme. This PhD project explores the use of code source as an historical source and notably the need for historicization and contextualization of code source to write a more informed history of the digital.