Oral histories offer invaluable insights into the past by embedding events within their lived social contexts and revealing perspectives often forgotten or neglected in archives. However, memories present a unique challenge for researchers because of their fragility: when the storytellers pass away, unrecorded stories can be lost forever.

The Legacy of “The Family of Man” Research Project at the C²DH in collaboration with the Centre National de l’Audiovisuel (CNA) and funded by the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR) began last year with the challenging Memory Quest to locate people who saw “The Family of Man” during its World Tour (1955-1963) and can remember it. Or at least, passed on their memories to families and friends in oral, written, or visual forms. Inherited recollections of visiting the exhibition, photographs, letters, and memorabilia related to the show, or even reflections on how the exhibition shaped their views on photography, humanity, or cultural identity are all welcome contributions to the project.

Building a Digital Crowdsourcing Platform

The first step was to set up a landing page for the crowdsourcing campaign to explain the research project and detail the type of information we hope to find, including some visuals to jog the memory. Since many might have known “The Family of Man” photographic collection from the exhibition catalogue rather than the show, we knew it was necessary to highlight the book cover. It was a popular gift through the 1950s and 60s and still sits in many homes today. In fact, it has never been out of print. Another important visual included on the landing page was a map depicting the international tour, with the locations and years when it was displayed in various cities.

To reach an international audience, it was also necessary to bypass language barriers. After all, the exhibition travelled to over 40 different countries. Currently in 11 different languages, the text of “The Family of Man” Crowdsourcing Campaign encourages people to contribute to a more inclusive and diverse collective memory of the exhibition.

Since people should feel free to contact the researchers in the language of their choice, the languages spoken by the team members are not specified. The team can supplement their linguistic abilities with AI translations to handle the expected diversity of languages.

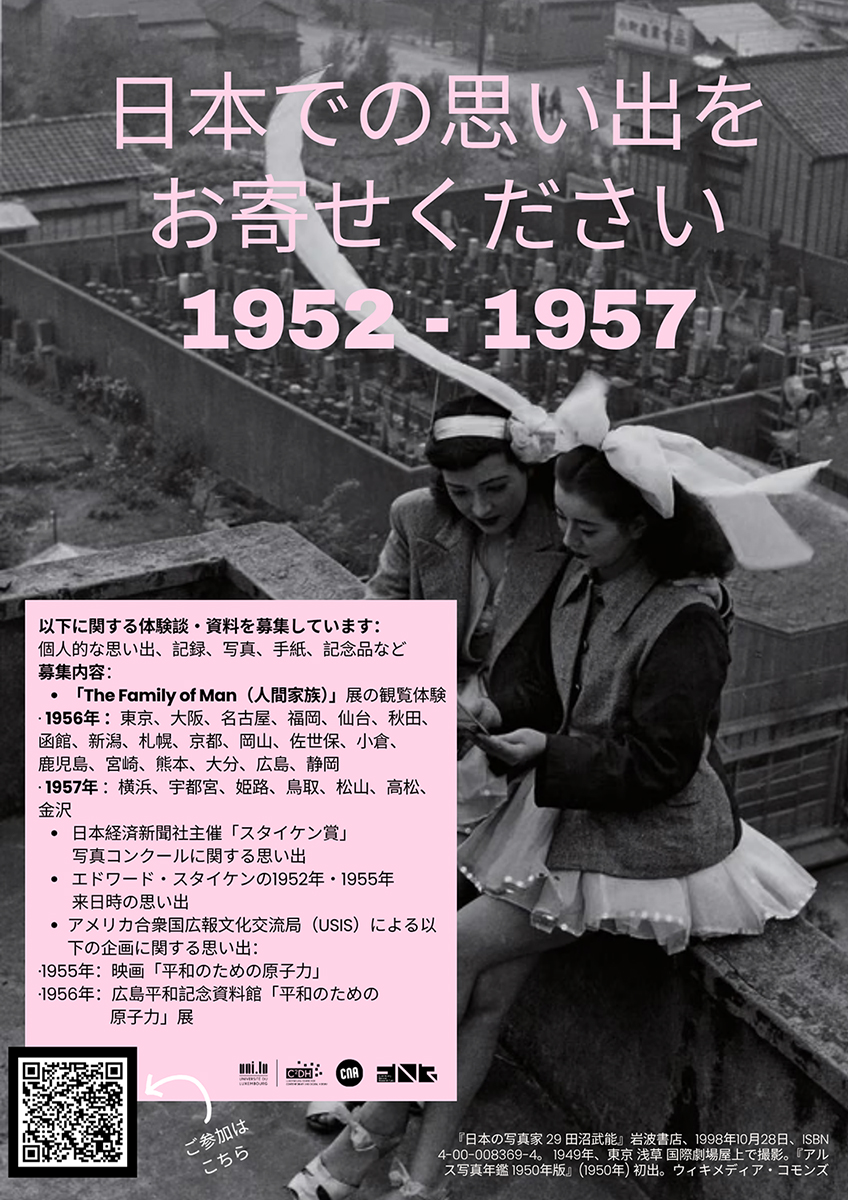

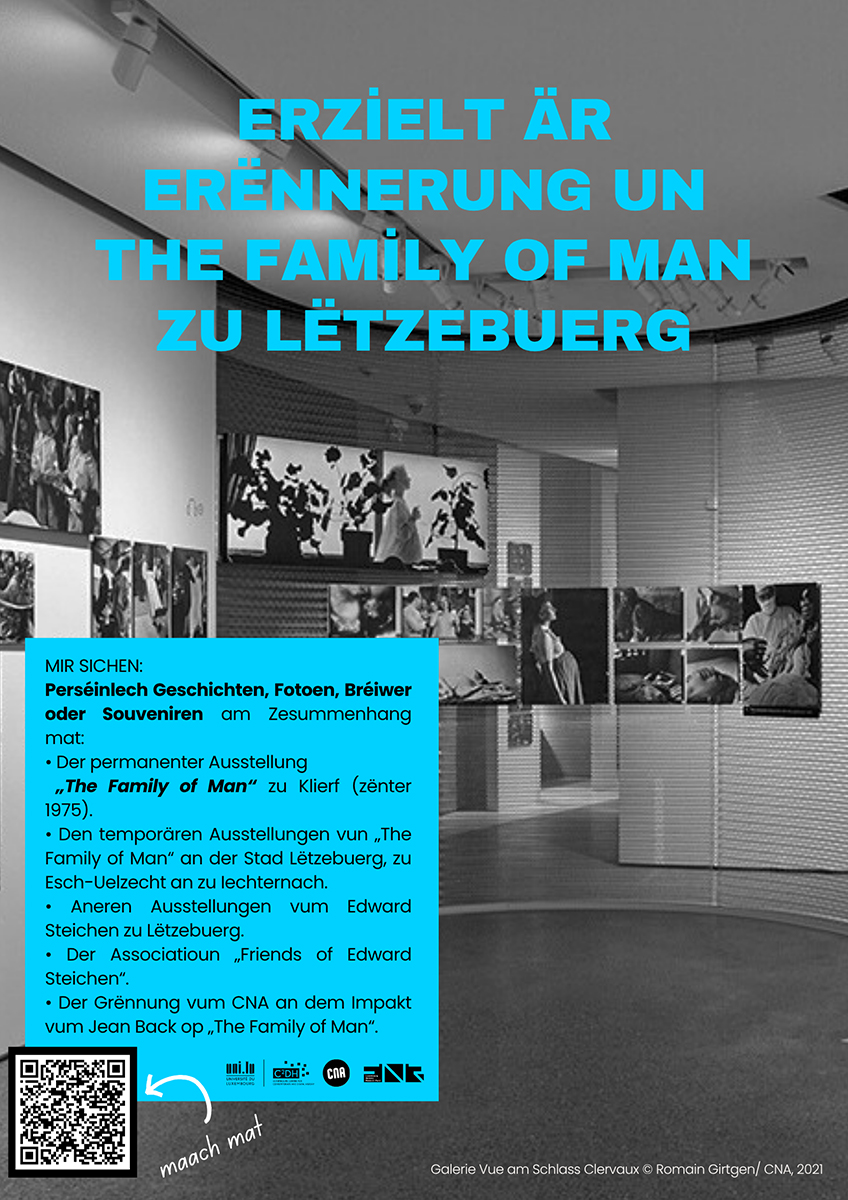

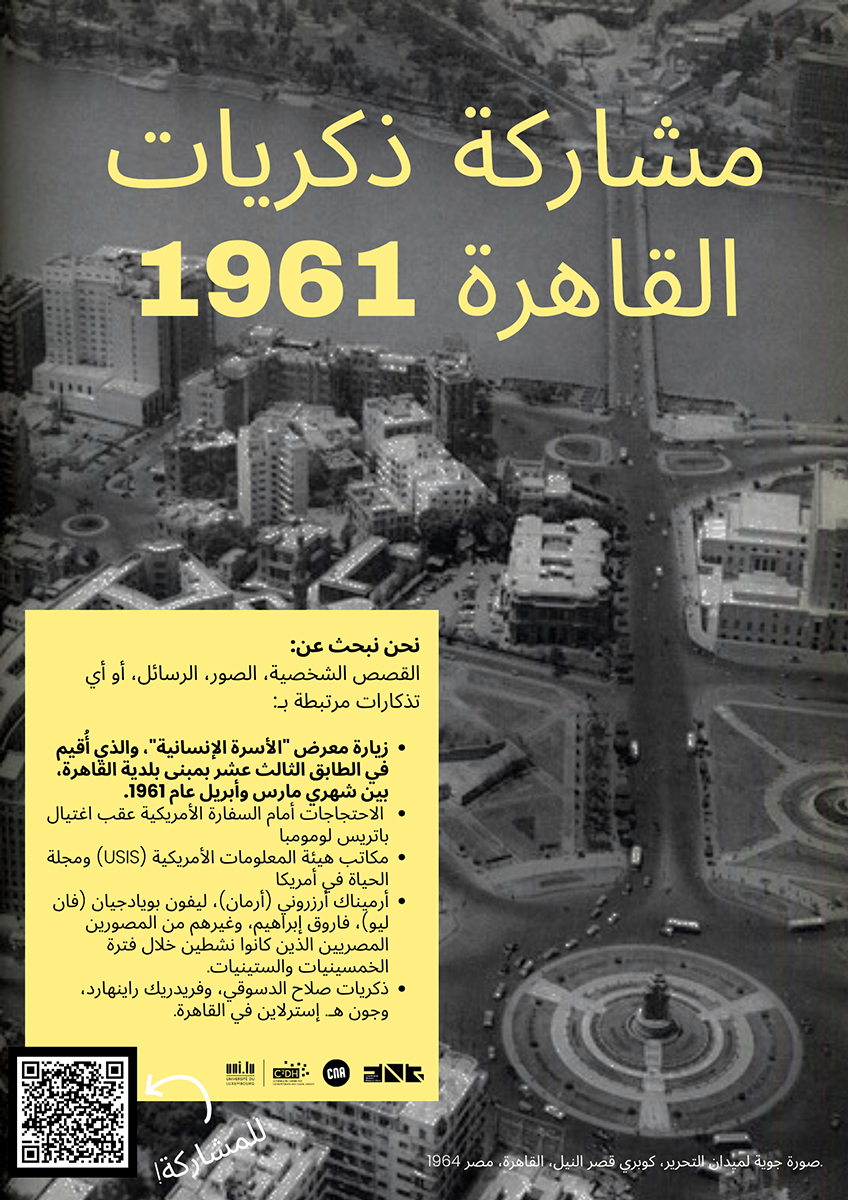

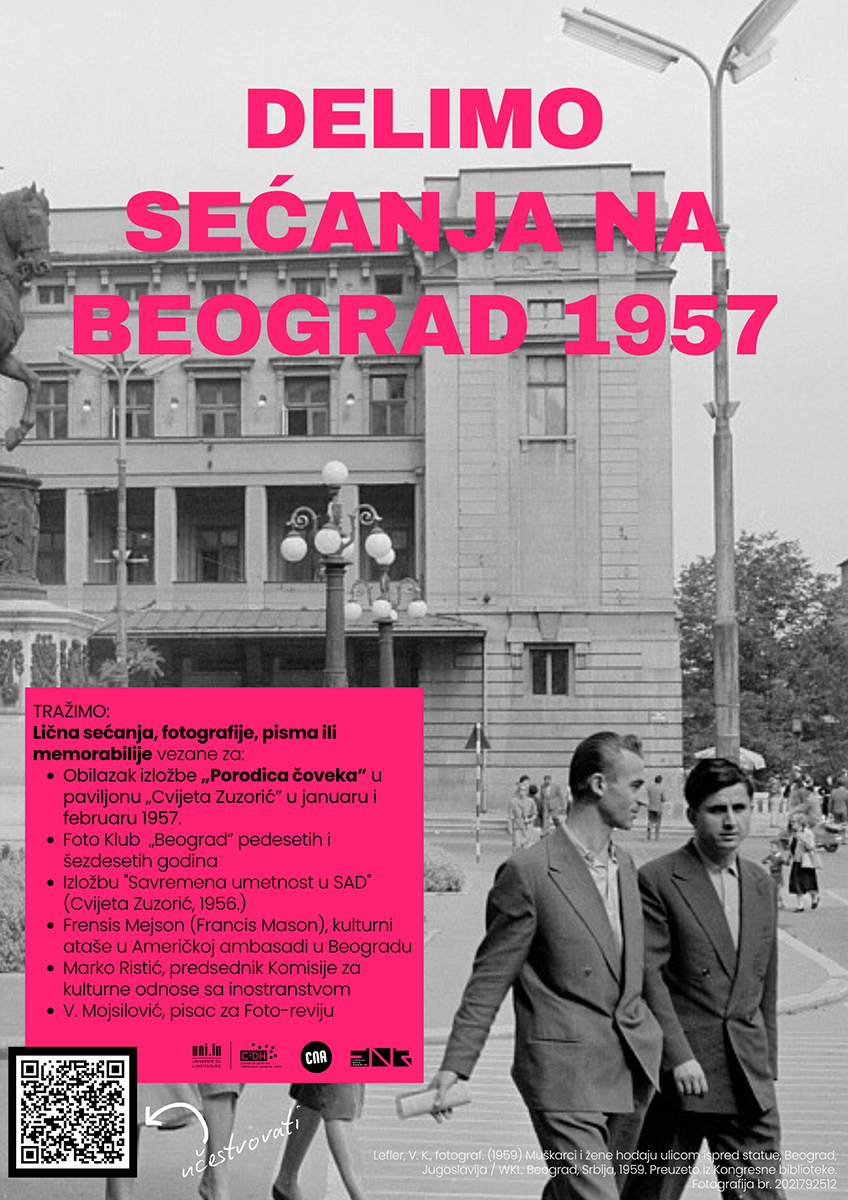

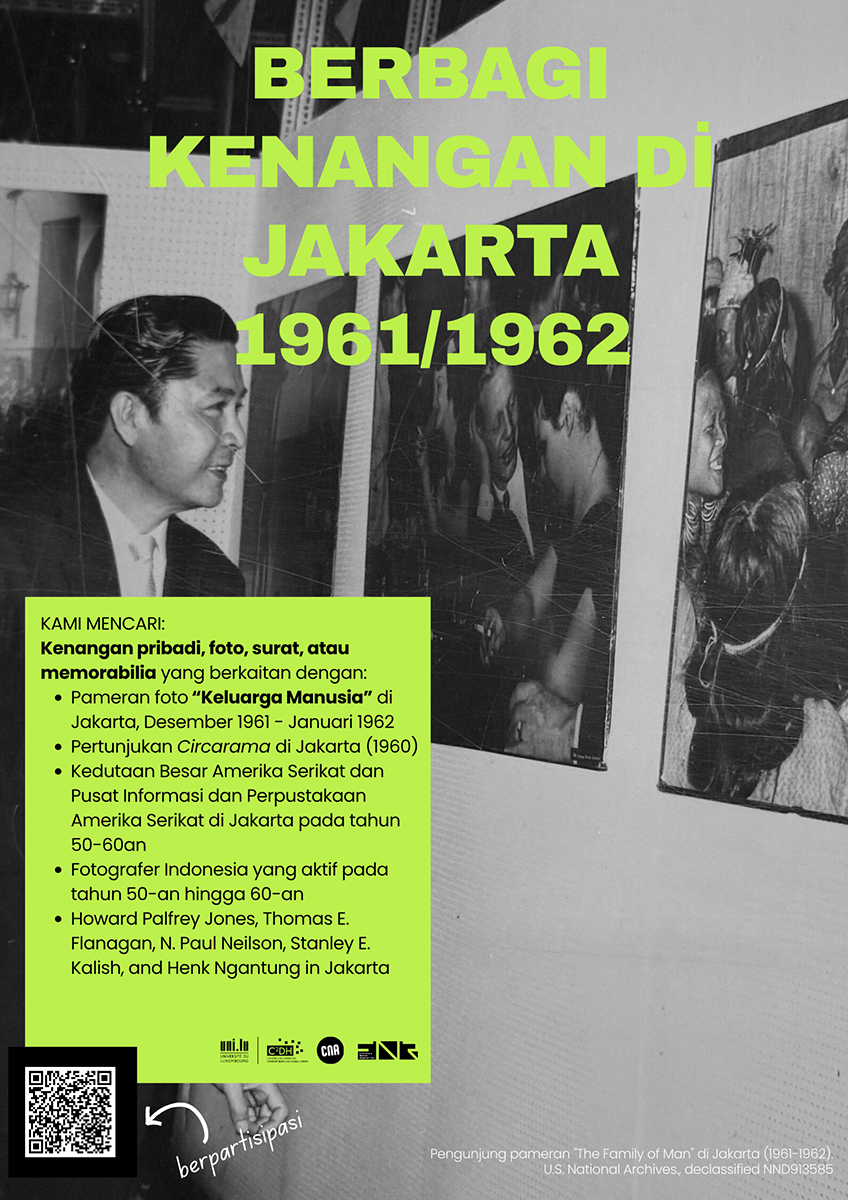

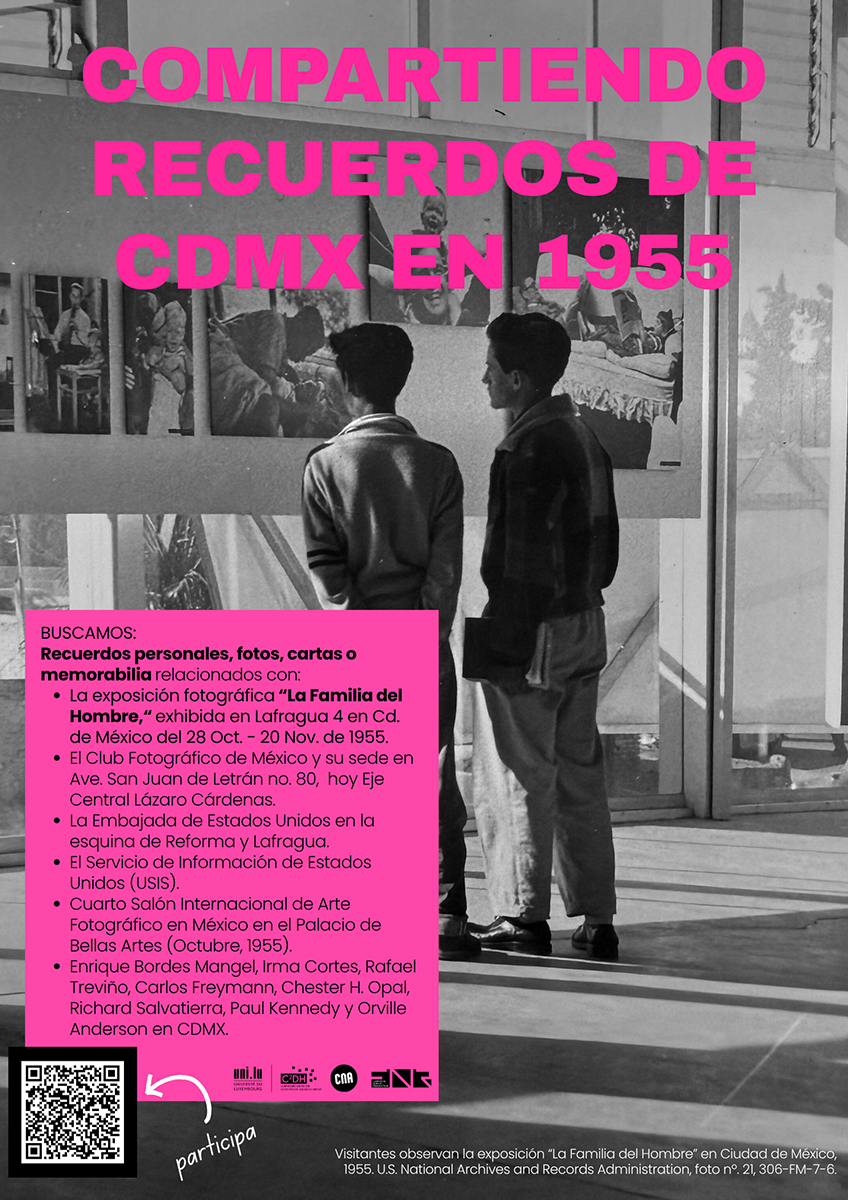

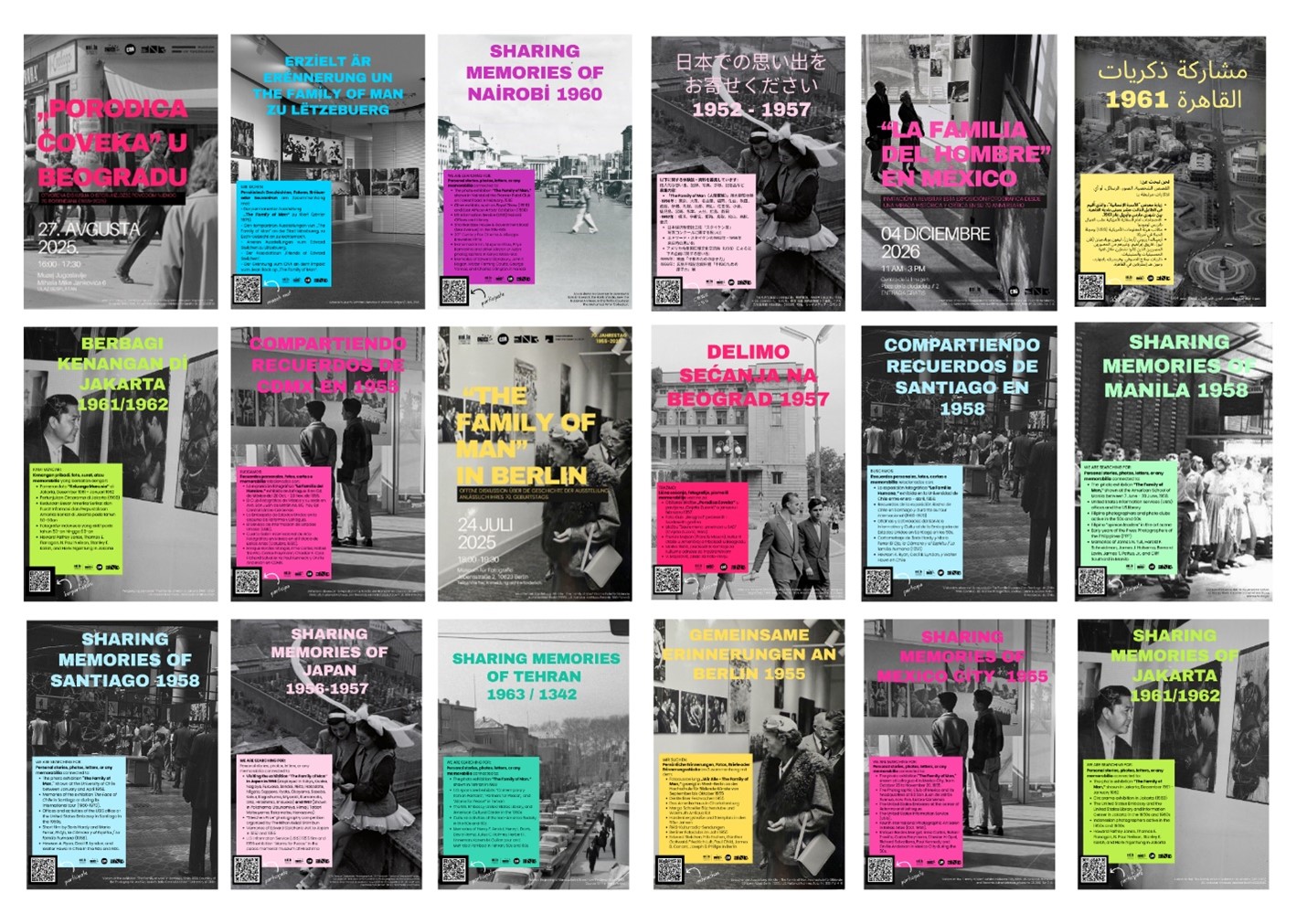

Finally, since the landing page only provides a general introduction, the project will rely on dedicated posters that localize the context, visualize it, and make it shareable. Below is a collage of these local posters, targeting cities like Santiago de Chile, Mexico City, Nairobi, Cairo, Jakarta, and Belgrade. These cities were chosen as case studies to ensure a balanced geographical representation across all continents, yet with a focus on the Global South. This is in response to the existing gap in the literature concerning the exhibition’s presentation in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Additional selection criteria included a diverse range of exhibition venues and visitor numbers. Making use of established networks and the possibilities of digital sharing, posters have also been created to reach beyond the primary locations and inquire about “The Family of Man” memories in Japan, the Philippines, and Tehran.

Collage of crowdsourcing and event posters for The Legacy of “The Family of Man” Research Project

It’s also important to note that digital crowdsourcing is planned as an amplifier, and does not replace in-person interactions. The collage includes posters of the first two open forum events organized on site: in Berlin (July 2025) and in Belgrade (August 2025). The crowdsourcing remains open after the in-person event and throughout the research project.

“Tell your story, on your terms”: Ethical Practices in Memory Collection

Ethical considerations are extremely important guiding factors for an appropriate oral history methodology. Taking note of the ACTIVE principles that guide our Public History axis at the University of Luxembourg, I made sure that the discussion forums were free and that the chosen dates and locations remained accessible. Before asking to collaborate with local institutions or individuals, I emphasized the project’s values of transparency and inclusivity, especially considering our positionality as a Luxembourgish institution conducting research in a wide range of locations with different economic and political realities. Adapting to the needs and wishes of the local partners continues to be the key driver of planning the on-site events. Providing me with a space to share my research project demands that they also benefit from the event as part of their cultural programming, a space to highlight their own work, or to connect their institutions with new publics.

Every individual who wishes to share their memories in an interview should sign a consent form specifying their rights to hold agency over the information provided and to withdraw from the research at any time if they wish to.

Most importantly, engagement doesn’t end at the research visit. The Legacy of “The Family of Man” Research Project will continue running until mid-2028, and continuous communication with the local contributors is also planned to accompany it during the whole duration of the project.

“Kindly spread the word”: Establishing Networks to Reach Wider Publics

Digital crowdsourcing in the international sphere comes with constant calls for participation across social media channels, newsletters, and personal connections. The research project recognizes that its success largely depends on the networks established at the locations of analysis. The ability to locate and connect with local archivists, curators, photo clubs, and photo historians can make all the difference in the accessibility of research sources.

Considering the case of Belgrade, the National Library of Serbia proved to be a rich source of information for exhibition reports, newspapers, and magazines of the period when “The Family of Man” was shown in Yugoslavia (1957 in Belgrade and 1958 in Zagreb). At first glance, without the ability to read Cyrillic or understand Serbo-Croatian, the finding aids can seem inaccessible and the process slow. AI translations resolve most immediate language barriers in online sources, and optical character recognition (OCR) technology integrated in translation apps provides a simple solution to navigate physical sources by scanning them with a cellphone. However, human connections should not be underestimated. Establishing a rapport with Biljana Bogdanović, responsible for interlibrary loans, months before the visit, streamlined understanding of the institutional system of Serbian archives and made the experience of visiting the library a collaborative and democratic effort, because Biljana and her colleagues could recommend additional sources that they considered relevant.

Likewise, personal networks led me to the Museum of Yugoslavia, which graciously hosted the open forum and invited people from their own network. Thanks to their targeted invitations, Mihailo Vasiljevic, doctoral researcher at the University of Belgrade, attended the event and alerted me to documents related to the Yugoslav Photo Association (Foto-savez Jugoslavije) held at the Archive of Yugoslavia and reviews of the show found in local magazines.

I hope to establish similar connections in the upcoming research visits to Mexico City (December 2025), Santiago de Chile (January 2026), and later visits to Nairobi, Cairo, and Jakarta.

“What if I don’t find anything?”: Absence of Information as Part of the Story

The lack of records and untapped memories is a recurrent concern in all research projects; however, intercontinental visits require larger budgets and constrain archival field trips to be done only once. Therefore, traveling to the location analysis and “not finding anything” is an understandably daunting prospect. The core strategy is, of course, preliminary preparation. The longer the project is visible in local networks, the higher the possibility of establishing connections with knowledgeable partners on site.

Nevertheless, a secondary aspect is the acceptance that people are on the move and might never learn about the project, memories are lost, archival conditions differ from place to place, and the importance given to a particular event might not have been as impactful as foreseen. Speaking of absences also helps understand the creation and transmission of historical narratives. Maybe the local photographic scene was not interested in “The Family of Man” and did not see fit to preserve records of it for 70 years, it is also possible that local governments who supported the show took the records or disposed of them when political shifts occurred, or the materiality of the documents and photographs did not survive the test of time if there were not enough resources to care for them.

Share your memories. Share this call. Help us learn more from local knowledge!