Kobosana te: boyokani ezali ya kala Luxembourg ná Kinshasa

As part of the COLUX research project, I traveled to Kinshasa (DR Congo) in November/December 2024 with a scholarship from the Fondation Zeilinger. The journey confronted me with the enduring legacies of colonialism and left me reflecting deeply on the role I occupy as a white or European historian working on the colonial past of Luxembourg.

In the following text, I shed light on the often overlooked or unknown entanglements between Luxembourg and the Congolese capital that I encountered during my journey. At this point, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to everyone who helped and supported me throughout my journey and stay – most notably Prof. Bruno Lapika Dimomfu, Pierre Turban Tudi, Jean Debéthel B. Bitumba, Cai Chen, the team at INACO, the administration of ‘Cité Kauka’, the Faculty of History at the University of Kinshasa, and the Secretariat of the C²DH.

Waiting for public transport. © Kevin Goergen, December 2024.

Born in Buschrodt – Buried in Ngaliema

Luxembourg’s colonial legacy in the Congo Basin can be traced back to the establishment of the trading post Léopoldville. Nicolas Grang (1854–1883) arrived in the Congo Basin in 1882 as part of the military expeditions led by Henry M. Stanley. Stanley named the station after the Belgian King Leopold II, who supported these expeditions in pursuit of his own interests. Born in Buschrodt, Grang became the first European buried in the ‘cimetière des pionniers’ on Monts Ngaliema – located in the western part of what is now Kinshasa.

Riding through the Monts Ngaliema by motorcycle. © Kevin Goergen, December 2024.

Following the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, the station Léopoldville was incorporated into the Congo Free State (1885–1908). During this period, at least 83 Luxembourgish citizens were active in the colony. The number rises to 90 if one also includes those who had acquired Belgian citizenship before departing, as well as those portrayed in the colonial narrative as ‘Luxembourgish pioneers’, despite having only minimal ties to the Grand Duchy.

In 1923, Léopoldville became the capital of the Belgian Congo (1908–1960). In 1966, the city was renamed Kinshasa as part of the Authenticité initiated by Congolese President Mobutu Sese Seko (1930–1997), adopting the name of a nearby village that had existed east of the original trading post.

From Monts Ngaliema, where Grang is buried, one can see Brazzaville, the capital of what is today the Republic of the Congo. Brazzaville was founded by Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza on behalf of the French state on the land of Téké King Makoko Ilboo. During the so-called ‘scramble for the Stanley Pool’ – particularly in the 1870s and 1880s – European powers competed for control over the region between the Atlantic coast and Pool Malebo. Missionaries played a significant role in advancing national and imperial ambitions during this period.

One such figure was Joseph Sand (1854–1926), who arrived in the Congo Basin in 1884 as a missionary with the Congregation of the Holy Spirit (Spiritans). He was instrumental in promoting French influence in what became French Congo. At the same time, his letters from the Congo Basin – ‘Briefe des Luxemburger Congo-Missionärs’ – were published in the Luxembourgish press, offering insights into colonial life and missionary work.

Looking across the Congo River to Brazzaville. © Kevin Goergen, November 2024.

In 1948, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the railway Matadi-Léopoldville, Luxembourg made its first official visit to the Belgian Congo. The delegation, led by Foreign Minister Joseph Bech (1887–1975), included Robert Als (1897-1991), Luxembourg’s minister in Brussels, and Mathias Thill (1890-1967), president of the Luxembourg Colonial Association (Cercle colonial luxembourgeois). During their visit they laid flowers at the grave of Nicolas Grang.

Eisem gro’ssen Kompatriot – Kompatriote monene na bino

In today’s courtyard of Kinshasa-Est train station stands a piece of history: ‘La Première locomotive de l’exploitation 1898’ (‘the first locomotive in service 1898’). On March 16 of that year, Luxembourgish engineer Nicolas Cito (1866–1949) drove this locomotive to the station at N’Dolo. Just four months later, the railway line was extended to the then-station Léopoldville-Est, marking the completion of the Matadi–Léopoldville railway after nearly a decade of construction.

Historic locomotive from 1898 preserved at Kinshasa-Est. © Kevin Goergen, November 2024.

At the station entrance, a large mural catches the eye. Above it reads the Latin phrase ‘Aperire Terram Gentibus’ (‘To open the land to the peoples’). This title alone reveals the perspective from which the mural was created. Painted during the colonial era to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the railway, the artwork exposes the racialized division of labour: European skilled workers and African labourers. Among the Europeans were several Luxembourgers; four of them died during the construction, along with 128 other Europeans. In contrast, the estimated 1 800 deaths among African and Asian workers remain a vague figure – one that underscores the colonial disregard for the lives of ‘non-white’ labourers in the relentless drive for colonial-capitalist expansion.

The Wikipedia article on Nicolas Cito (1866–1949) is available only in Luxembourgish and Lingala. Yet, Cito left enduring physical traces and a collective memory in Luxembourg and the DR Congo. A commemorative plaque honouring Cito was unveiled in 1938 in Bascharage, a village in Luxembourg. It bears the inscription: ‘Eisem gro’ssen Kompatriot dem Nicolas Cito Ingene’er Kolonial-Pionne’er Generalkonsul vu Letzeburg’ (‘To our great compatriot Nicolas Cito, engineer, colonial pioneer, and General Consul of Luxembourg’). This monument has been, and continues to be, a focal point in Luxembourg’s ongoing debate about its colonial legacy and historical entanglements.

If you ask people in Kinshasa today – more precisely in or around the Kauka neighborhood – whether they know Nicolas Cito or what they associate with his name, the most common answer would likely be ‘Cité Cito’. Established in 1948 as ‘Camp Nicolas Cito’, the neigboorhood was built to house Congolese workers of the OTRACO (Office d’Exploitation des Transports Coloniaux). In the early 1950s, it primarily housed navigators, machinists, and their families – residency required having at least one child. By the 1970s, ONATRA (Office National des Transports) employees could access affordable housing loans, and in 1974, the area was renamed ‘Cité Kauka’. The name ‘Kauka’ refers to a dredger ship used for river maintenance. Today, the neighborhood is still home to many former ONATRA employees and their families. Among the older residents, the name Nicolas Cito still resonates.

Colonial Traces – Shared Legacy

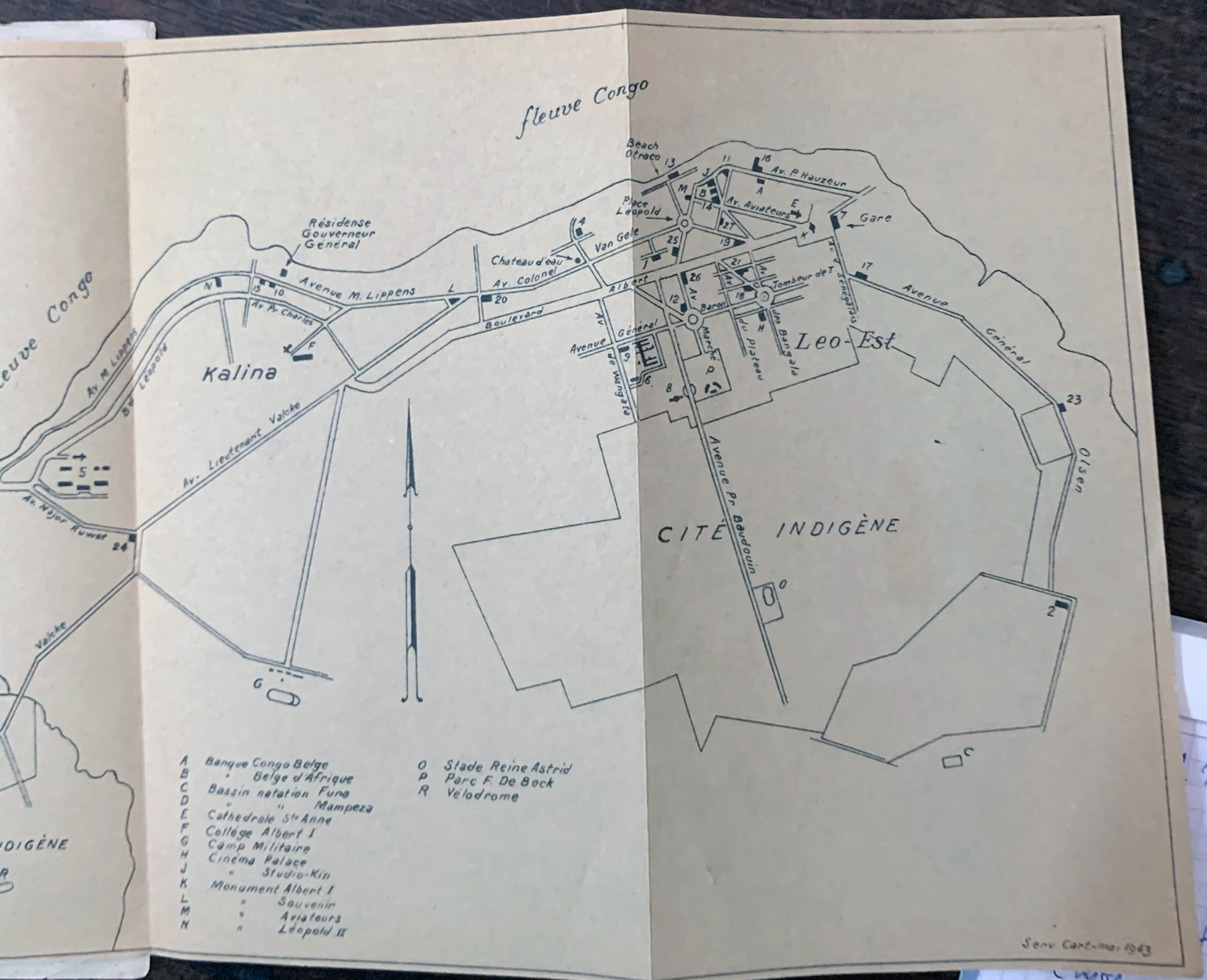

Brochure for white newcomers to Léopoldville in the 1950s, photographed at National Archives, INACO. © Kevin Goergen, November 2024.

Walking through the streets of Kinshasa today – especially in Gombé, formerly Kalina and the European quarter during the colonial era – there is little at first glance to suggest that in the 1950s, an average of 134 Luxembourgers lived in the Léopoldville district, many of them concentrated in what is now the commune of Gombé.

The district, with its modern high-rises and remnants of colonial architecture, contrasts sharply with the bustling Cités where most Congolese reside. Gombé has become a hub for non-African communities, with a notable presence of Lebanese, Indian, and Chinese residents. As historian David Van Reybrouck noted in Congo: The Epic History of a People, ‘a generation is growing up in Kinshasa today for whom a European is more exotic than a Chinese’. The city’s spatial and social divisions reflect a pattern that has persisted from the colonial into the postcolonial era.

‘Ezo’ Roundabout, located in the so-called ‘Cité’. © Kevin Goergen, December 2024.

In the heart of ‘Kapela’, likely considered the true centre of Kinshasa. © Kevin Goergen, November 2024.

During the colonial period and into the early years of Congolese independence, Luxembourgers probably played a more visible role in Gombé’s commercial life. Around today’s avenue de l’équateur and avenue de la paix, several businesses were operated by Luxembourgers. At the corner of avenue des cataractes located the first Luxembourg consulate in the 1960s. The idea of establishing a consular presence in the Belgian Congo sparked debate within Luxembourg’s colonial milieu. While the CCL (Cercle colonial luxembourgeois) advocated for it, figures like Nicolas Cito – then General Consul in Brussels – opposed it.

One enduring legacy is the Pâtisserie Nouvelle, founded in 1941 by René Delvaux (1911-1988). Though now owned by a French proprietor, the bakery still operates today. Delvaux also co-owned a business called REDELCO with his Swiss colleague. In the 1940s and 1950s, his establishments became a welcoming point for new Luxembourgers arriving in the Congo Basin. Even after independence, his businesses remained active – for instance, Théodore Pescatore (1912–1999) continued working for the company in the 1960s.

View of ‘Pâtisserie Nouvelle’ in Gombé. © Kevin Goergen, December 2024.

Walking along ‘Avenue de l’équateur’, likely the centre of Luxembourgish commercial life in 1950s Léopoldville. © Kevin Goergen, December 2024.

Some Luxembourgers found work in the gastronomy, including at the once-prestigious Hotel Le Regina, now abandoned on the Boulevard du 30 Juin. Others held positions in public institutions: Victor Conzemius (1918-1979), for example, served as director of the Léopoldville Zoo during the 1950s, Guillaume Pauly (1899-1978) was a leading doctor at the Clinique Reine Elisabeth (renamed Clinique Ngaliema in 1971), and Jules Campill (1887–1956) worked as a magistrate.

The latter’s residence stood on the same street as the CONGOLUX store, which was owned by Jean-Pierre Schiltz (1907–1958). Schiltz distributed Luxembourgish products throughout the Belgian Congo and to Brazzaville. He also represented Luxembourg at the 1951 commercial fair in Léopoldville, where the Luxembourgish stand was proudly decorated with the Grand Duchy’s flag and photographs of the Grand Duchess.

Jean-Pierre Maroldt (1918-1963) operated a photography shop on what is now Avenue Tombalbaye. In Limete, further southeast, Isaac Eisner (1903-1970) ran an import-export business, while Marcel Hannes (1914-1964) sought a loan from the SCCI (Société de Crédit au Colonat et à l’Industrie) to build a hotel in the then new commune of Limete.

The Luxembourgish footprint in Kinshasa is still traceable – subtle traces and silent witnesses to a largely forgotten chapter of shared history between Luxembourg and the Congo.

Contemporary Voids – Historical Tasks

Countries like Luxembourg, though never formal colonial powers, remain deeply entangled in Europe’s colonial history and legacy. Depending on the context, this past is either emphasized or conveniently overlooked. Especially in political discourse, such selective memory enables elites to distance themselves from post- and neocolonial dynamics in which they are nonetheless embedded. Yet colonialism was never merely a national endeavour – it was a pan-European project, fuelled by global capitalism, transnational cooperation, and shared ambitions, including the prestige it conferred on participating states.

During my stay in Kinshasa, the Congo was experiencing widespread armed conflict, particularly in the eastern provinces of South and North Kivu. However, in the Kwango province near Kinshasa, clashes between security forces and Mobondo fighters resulted in several deaths and arrests. Meanwhile, in the east, the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) was engaged in battles with various so-called rebel groups, including Red Tabara, Twigwaneho-Ngumino, and the March 23 Movement (M23), which captured Goma in late January 2025. These events sparked protests in Kinshasa against Ruanda and international inaction, with demonstrators targeting several foreign embassies. Globally, attention turned to Rwanda’s alleged support for M23, and Luxembourg’s foreign policy – particularly Xavier Bettel’s stance toward Rwanda – came under scrutiny. In Luxembourg, protests were largely limited to members of the Congolese diaspora. Yet, conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa – such as those in eastern Congo – have received strikingly limited public attention in Luxembourg, particularly when compared to the significantly greater visibility and concern given to conflicts in other parts of the world. The conflict in the DR Congo is often reduced to a struggle over resources, sidelining African perspectives, the history of the area and political complexities.

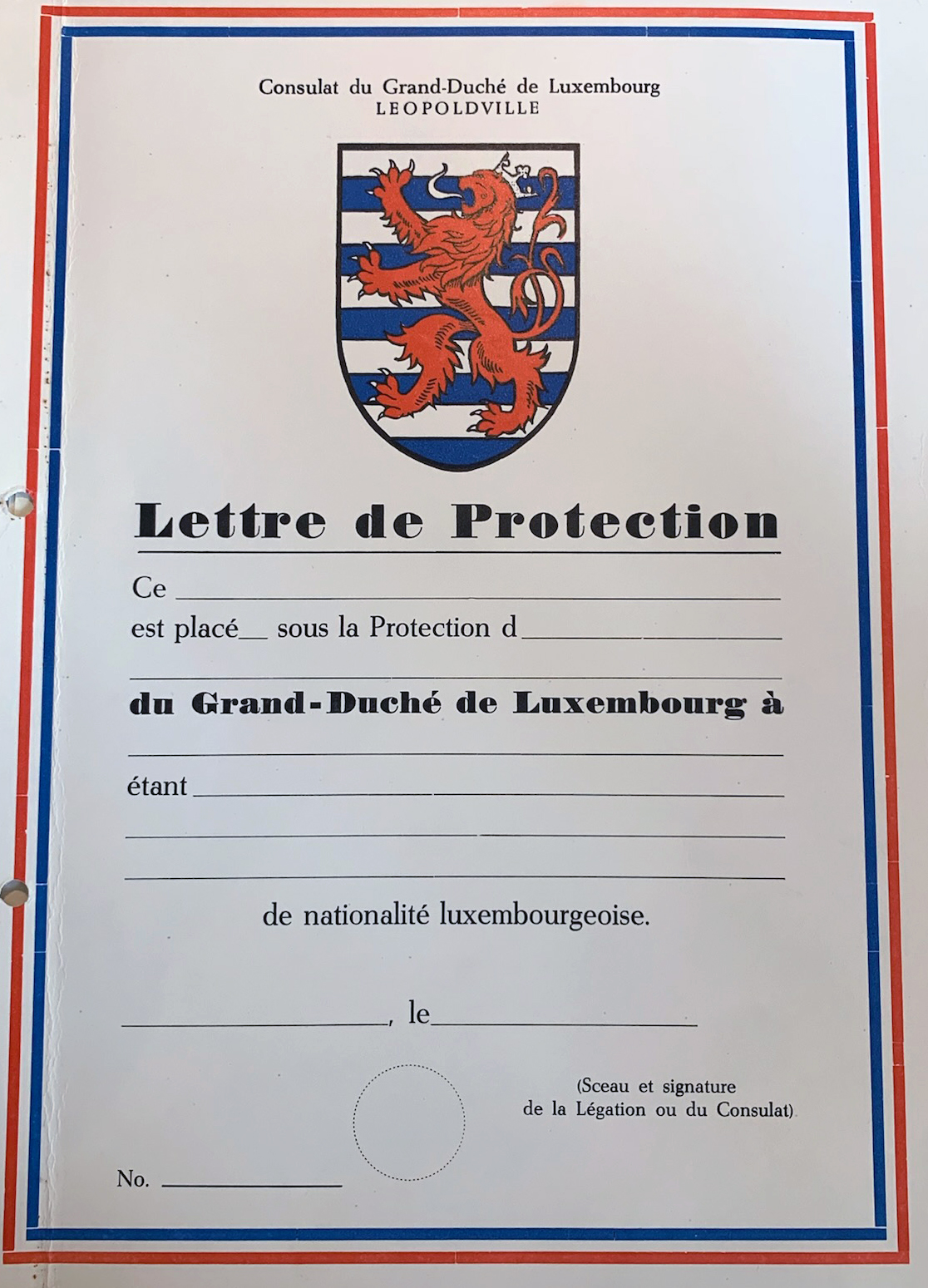

Lettre de Protection’ issued after the independence of the Congo on June 30, 1960.

Demonstration in Luxembourg City against the violent conflict in eastern Congo. © Kevin Goergen, February 2025.

Historically, Luxembourg may be more closely connected to the Belgian Congo than to any other colony. Yet these historical ties are often portrayed as distant or even non-existent in relation to the present-day DR Congo. This reflects a certain privilege of a state that benefited from colonial entanglements without bearing the responsibilities of colonialism or formal colonial rule after independence. Unlike Belgium, which in the 1950s and after Congolese independence offered scholarships to Congolese students and saw the emergence of communities like Matongé in Brussels, Luxembourg has not provided similar opportunities to Congolese. In Belgium, the painful history of the so-called ‘Métis’ has been publicly acknowledged and political debated. In contrast, the children of Luxembourgish fathers in Congo – most of whom were never recognize – remain largely invisible. It is unknown how many Congolese, like Brazilians and Americans under the 2008 nationality law, could have claimed Luxembourgish citizenship by proving descent from a Luxembourgish ancestor as of January 1, 1900. Ultimately, Luxembourg’s colonial past remains insufficiently examined, with significant gaps in the analysis of colonial sources, both private and public archival materials, and in the inclusion of perspectives from descendants and other unheard voices.

History, the study of the past, must bridge past and present and shed light on forgotten or uncomfortable truths. In the 20th century, colonial projects undertaken by the state, the economy, and the Church were often seen as symbols of prestige. Today, the situation has reversed – especially for European countries without formal colonial possessions, distancing themselves from this legacy is relatively easy. Yet engaging with colonialism is essential to addressing the historical omissions that underpin contemporary discourse.