It all started with a series of postcards sent by Luxembourgers living in Romania to their relatives back home. Thanks to the precise work of historians to find the root of these postcards, we know that Romania, today known as a land of emigration, was once a labour destination for Luxembourger of all social classes.

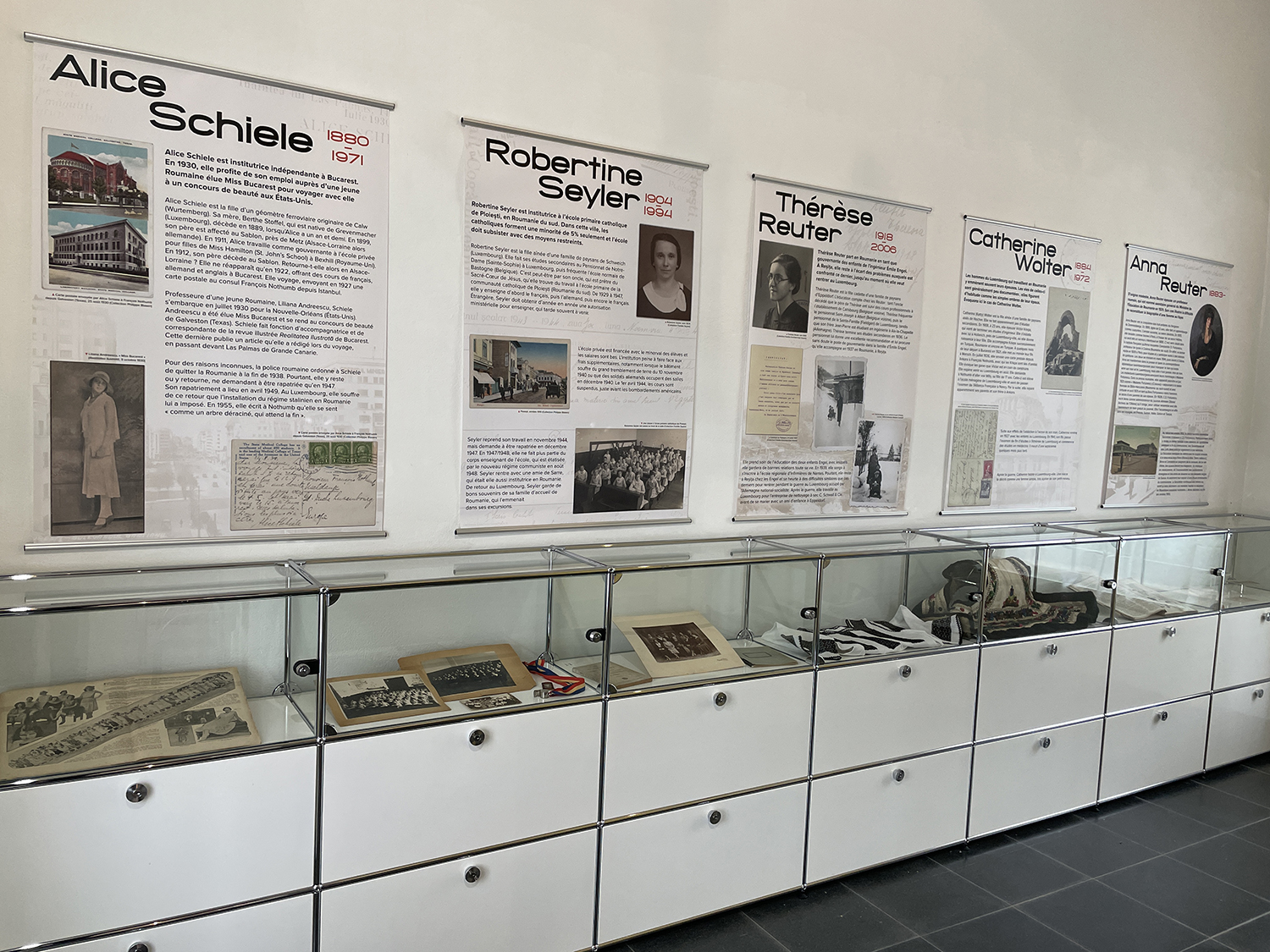

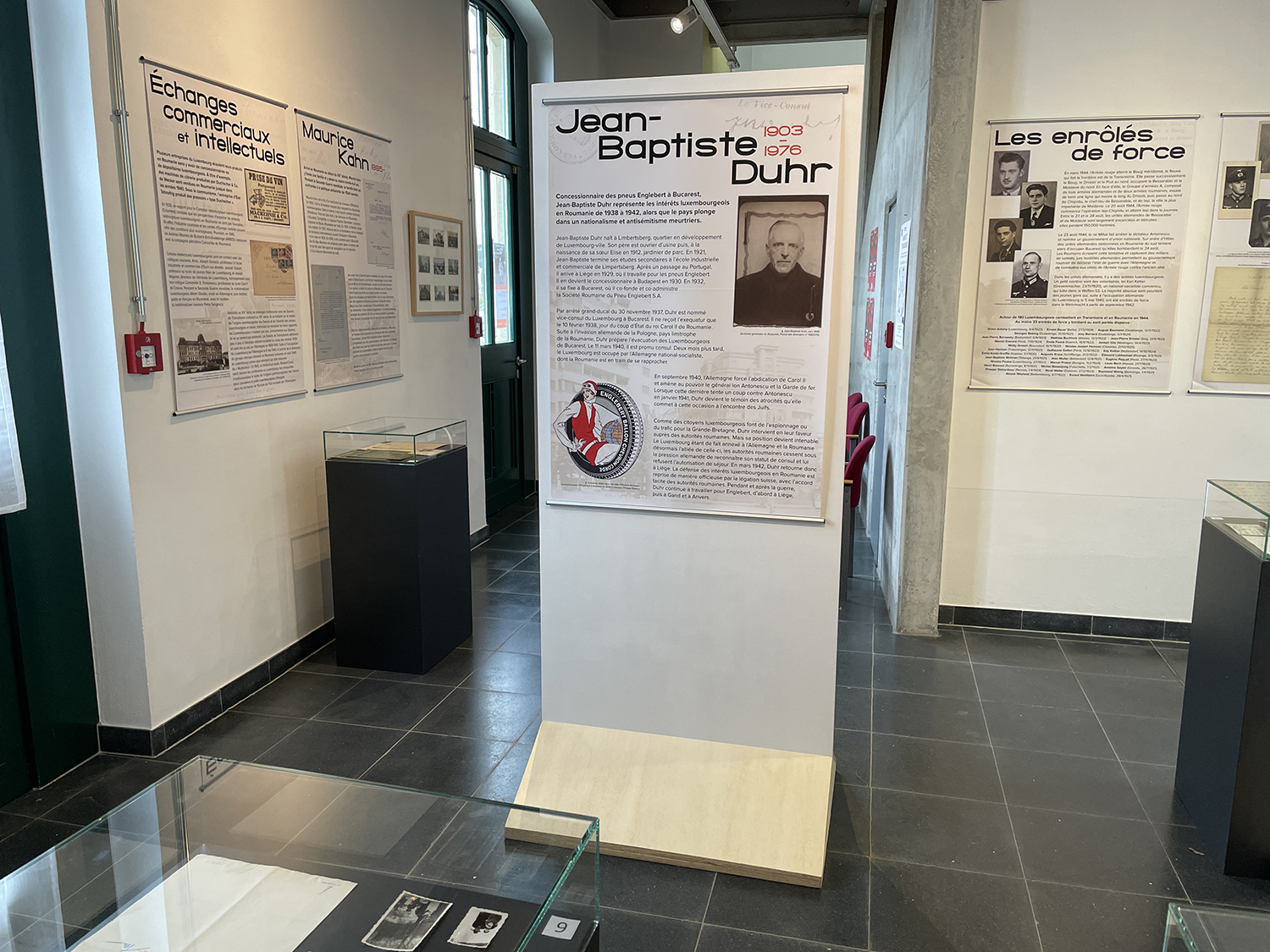

Philippe Henri Blasen, a historian at the Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C²DH), uncovered the stories of around 20 people from Luxembourg who moved to Romania for work between 1890 and 1950, and was able to piece together their biographies. Their stories are currently presented in the exhibition “Arbres fruitiers, tunnels ferroviaires et tubes sans soudures. Présence luxembourgeoise en Roumanie (1890-1950)” (Fruit trees, railway tunnels and seamless tubes. The presence of Luxembourgers in Romania (1890-1950), produced by the Documentation Centre for Human Migration (CDMH) in Dudelange in partnership with the C²DH.

A series of postcards from the 1900s spotted by the actress Larisa Faber at a jumble sale set the stage for the story. The cards had been sent by a certain Henri Kintzelé from Câmpina, a town in Romania’s oil region, to his father in Godbrange, in the Luxembourg municipality of Junglinster. Research uncovered that Henri Kintzelé had left Luxembourg as an unqualified labourer and travelled to Romania, where he probably learned the profession of drilling machine setter-operator on the job. He would subsequently practise this trade in France and Belgium.

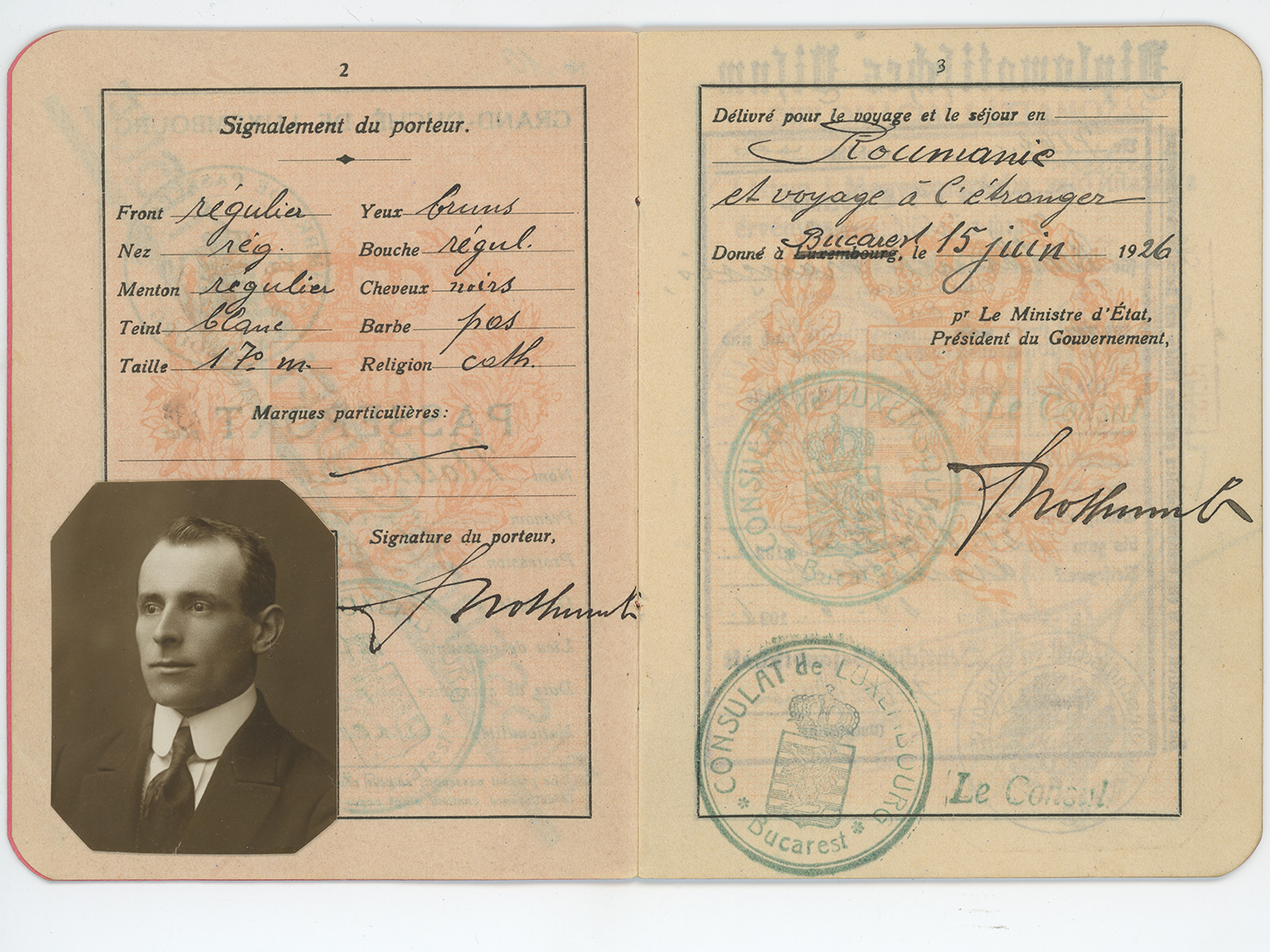

The research process began again in earnest after the discovery of correspondence from François Nothumb, who became Luxembourg’s first consular representative in Romania in 1921. Philippe Blasen gradually managed to piece together the stories of engineers, merchants, governesses and an arborist, in varying levels of detail. These findings clearly showed that Romania was part of the European labour market before the “iron curtain” divided Europe in two, and that the country, today known as a land of emigration, was once a destination for people from Luxembourg, of all social classes, seeking work.

Charles Haas, specialist in seamless tubes

Charles Haas, originally from Kayl, was the director of the company “Aciéries et Usines à Tubes de la Sarre” when the Saar region voted in a referendum in 1935 to rejoin Germany, then under the rule of the National Socialist Party. Most Luxembourgers chose to leave the Saar after the referendum. Haas was lucky: the leading industrialist Nicolae Malaxa was looking for a specialist in seamless tubes to manufacture this type of product in Bucharest. Haas, a recognised expert in the field, was recruited to build and lead the new factory. He was given a very generous salary and the company rented a mansion for his family in the Romanian capital. His wife Pauline Haas and their two daughters became involved in Bucharest’s high society life. Everything seemed to be going perfectly when the Iron Guard, an ultranationalist antisemitic movement, came to power in September 1940. Haas was criticised in the movement’s newspaper and resigned from the board of the Aciéries et Domaines de Reșița, the major Romanian steel company. During the war, he tried to reach the United States but ended up in Bilbao, Spain. His business affairs in Romania were managed by his wife, who did not leave the country until 1946.

Charles Haas

Jean-Nicolas Krier, arborist

Jean-Nicolas Krier, the son of farmers in Bertrange, studied arboriculture in Geisenheim, on the Rhine. He applied for work in Romania and was recruited in 1897 as a horticulturalist in a state nursery near Iași, a large city in the east of the country. He rose through the ranks to direct the company, then taught arboriculture at an agricultural college in Bucharest, where he was subsequently appointed as deputy director. He was highly regarded by the chambers of agriculture, becoming an adviser there in 1933. Two years later he even launched his own arboriculture journal, and in 1939 he represented Romania at an international agriculture conference. In 1945, Krier died in the country where he had lived for 48 years. Although he gained considerable visibility in the Romanian press throughout his life, until now Krier has been entirely absent from Luxembourg historiography.

Transylvanian Saxons – cousins?

The exhibition also looks at long-distance trade and intellectual exchanges. It especially focuses on interactions between Luxembourgish and Saxon intellectuals in Transylvania. These began in the late 19th century, when the Saxons, a German group that had arrived in Transylvania in stages from the 13th century onwards, “discovered” their Luxembourgish origins, which in practice have still never actually been proven.

The problem was that the Transylvanian Saxons developed close relations with the German state from that period onwards, and they largely supported National Socialism in the 1930s. In their view, the fact that they were Germans and of Luxembourgish origin showed that Luxembourgers must also be Germans. On this basis, in August 1940, the press outlet of the German ethnic group in Romania presented the German occupation of Luxembourg as a return to the “Mutterland”, and in 1942 a Saxon intellectual named Richard Csaki called on the people of Luxembourg to emigrate to the eastern regions of Germany in a series of lectures in which he spoke about the supposed Luxembourgish roots of the Saxons.

The exhibition developed by Philippe Blasen and Bronwyn Cragg is open from Thursday to Sunday, 3 to 6pm, until 16 February 2025, at Dudelange Gare-Usines (free entry).

About the researcher