“The Blue Marble”

Floating freely against the black background of space, the blue globe shines: “The Blue Marble”, taken on December 7, 1972, about 29,000 kilometres from Earth by the crew of Apollo 17 on their way to the moon. The analogue Hasselblad medium-format camera with f-2.8/80 mm fixed focal length from Zeiss captures the entire Earth in one image, showing almost all of Africa, the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean with a typhoon forming over India.

It is a legendary photograph that has become part of the global cultural heritage. An icon, an image that is 50 years old and has shaped generations and continues to do so. Perhaps this is also due to the fact that 1972 was the birth year of a global environmental movement: in its report “Limits to Growth”, the Club of Rome warned against a world geared towards material growth. Today we know that these first computer simulations, which show that the resources available to us are finite, were astonishingly plausible and accurate.

Global society is becoming richer and healthier – the environment more fragile

Around four billion people lived in the world in 1972. Today there are twice as many, eight billion. The global gross national product has risen from 4 to 96 trillion US dollars and CO2 emissions have risen from 20 to 40 billion tons of CO2 equivalents. Earth Overshoot Day, the day on which the Earth’s natural capacity for producing renewable resources or naturally removing emissions is exhausted for the year, moved from December 14 to July 28. Since 1972, our global society has grown, become richer and healthier – which can be seen, among other things, in the significantly lower infant mortality rate. All at the expense of a fragile but also very diverse environment and a large number of the blue sphere’s resources.

A picture stands for limitations, diversity and change

Although no one has taken such a photo since then, we take this image for granted. Google Earth presents it on the start screen and allows you to zoom in to any point on the earth. As macabre as it sounds, we can be there live when polar ice and high mountain glaciers melt and disappear. Satellites show how groundwater levels in India sink to unreachable depths over decades due to irrigation farming and how the water levels of Lake Mead fall inexorably. We have the opportunity to follow the progressive fragmentation of the rain forest on our own laptops. We can see how palm oil plantations are spreading in Indonesia and how dust and dirt are causing health problems in metropolitan areas such as Beijing and Delhi. Anyone can access all this information on their own computer with a few cleverly formulated search queries. With a few search queries, you can see how amazingly diverse the world is – not only in terms of dwindling biodiversity, but also in terms of how we humans live together. The Dollar Street project illustrates how living conditions differ.

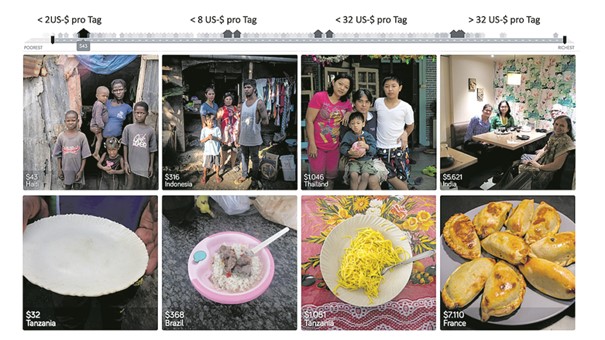

The Dollar Street project illustrates the living conditions of people around the world with individual incomes ranging from under USD 2 per day to over USD 32 per day in a wide variety of countries

There are still many countries in the world where the population has to get by on less than 2,000 calories a day – that’s 800 million people suffering from hunger. By comparison, people in the global North consume up to 8,000 calories a day. So, when discussing the food and nutrition situation, it is primarily a question of distribution and consumption – not of production or its increase. So perhaps it is now time to interpret the image of the Blue Marble differently: Yes, it shows the finiteness of the planet, it is a reminder of the diversity of life on it, but it is also a symbol of how closely intertwined and interdependent it is. Over the past 50 years, the world has grown together in terms of information technology, albeit very unevenly distributed. 5.2 billion people – 93 percent of them in North America, but only 43 percent in Africa – have access to the Internet and are able to collect and combine a wide variety of information.

Technologies bring about change

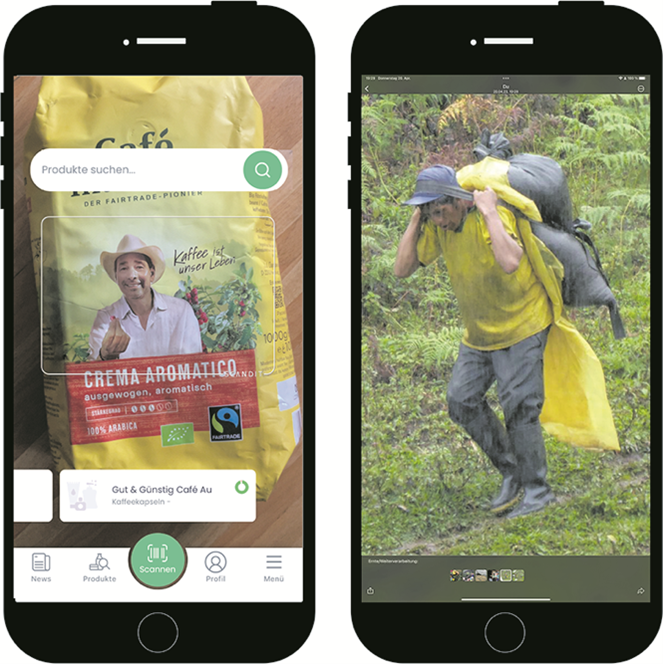

So, could we succeed in aligning this tremendous progress of information technology convergence – which is certainly not yet complete – with the management of our planet’s resources in such a way that we do justice to what they are: limited and largely common goods? Let’s dream a little. Could we implement a supply chain monitoring system that records the flow of goods from production on a farm to the consumer (keyword “supply chain due diligence law”)? Certainly not for every product, for every producer and at every point in time. But the technology is there and with it the possibility of spot checks, such as speed checks on the highway. It is also no longer a matter of years before an app not only displays the Nutri-Score and possible intolerances, but also the production situation in the country of origin by linking to image databases available worldwide. The image below shows what something like this could look like. Would it be possible to identify where illegal fishing is taking place? Yes, of course. With high-resolution night-time images which were intended to detect clouds in order to improve weather forecasts, this would certainly be possible.

Will apps one day be able to show us the production conditions of our consumer goods?

Together with the information on their financing (70 percent of the funding for illegal fishing comes from so-called tax havens), there are certainly interesting opportunities to intervene and impose sanctions. And finally, one could also imagine a community of states concluding that it would make sense to jointly lease Brazil’s rain forest for climate protection reasons. Of course, every square meter not cleared would mean an annual payment of real money to the Brazilian state. The decisive factor here is not the consumption of a crate of beer, as a German brewery once tried to convince its customers in an advertising campaign, but the fact that the global community is in a position to control every square meter of rain forest. The idea is not quite so far-fetched. Every prospecting company for rare earths, oil or gas pays such a lease for the area in which it is active.

Unlimited material growth is ultimately not possible

For 50 years, “The Blue Marble” has stood like no other image for the message that we must treat our very fragile Earth habitat with care. Even if you have heard the slogan of many Fridays for Future activists many times, it remains true: “We only have this one Earth.” It’s the 2022 version of a quote from Kenneth E. Boulding, John F. Kennedy’s environmental advisor, who held office long before “The Blue Marble” was captured on a movie reel: “Anyone who thinks exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

Originally published in German at MINTzirkel

Recommended reading

Rosling, Hans, Anna Rosling Rönnlund, und Ola Rosling. Factfulness: wie wir lernen, die Welt so zu sehen, wie sie wirklich ist. Übersetzt von Hans Freundl, Hans-Peter Remmler, und Albrecht Schreiber. 8. Auflage, Ungekürzte Ausgabe. Berlin: Ullstein, 2020.

Wiegandt, Klaus, Hrsg. 3 Grad mehr: Ein Blick in die drohende Heißzeit und wie uns die Natur helfen kann, sie zu verhindern. München: oekom verlag, 2022.

Ritchie, Hannah. Hoffnung für Verzweifelte: wie wir als erste Generation die Erde zu einem besseren Ort machen. Übersetzt von Marlene Fleißig. München: Piper, 2024.