Berlin-based artist Max Kreis recently spent two weeks on campus Belval as part of his Casino Display residency. His exchanges with researchers from the University of Luxembourg fed an artistic project dedicated to memory and relying heavily on artificial intelligence. On 23 October, a symposium at Casino (14:00 – 18:00) will conclude this residency. It will be the occasion to present the first outcomes of his stay in Luxembourg and to gather artists and scientists once more.

Inviting artists on campus

This residency is a collaboration between Casino Display and the University of Luxembourg. As there is currently no art faculty in the country, the idea behind this new initiative is to bring artists on campus to facilitate exchanges with scientists. “Programmes like this one already exist in several scientific institutions such as CERN and MIT, and we know from experience that encounters between researchers and artists can be mutually beneficial,” explains Anouk Wies, strategic advisor for cultural affairs at the university. “Max Kreis is the first artist staying on campus Belval as part of this collaboration and hopefully many others will join us for a residency in the coming years.”

A first artist well-versed in science and technology

For Max Kreis, immersing himself in science is not exactly a brand-new experience. The young artist, who trained in IT before his art studies, has been working with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for the past six years. “After studying light art and installations, I got hooked on AI and generative art as it combines several of my interests: art, science and technology,” he recalls. His work is often based on scientific publications and some of his previous projects were done in collaborations with neuroscientists from Charité Berlin.

As he enjoys using new technologies to turn science into striking visuals, Max Kreis felt right at home when joining the Imaging AI group led by Dr Andreas Husch at the Luxembourg Centre for Systems Biomedicine (LCSB): “This was really a good match! We worked well together, I felt integrated into the team and their expertise in machine learning and neuroscience was extremely valuable.” The experience was so positive that he hopes to keep working with the team on more long-term projects, bringing his own skills as an added value to scientific endeavours such as the development of a visual model for tumour growth.

Additional exchanges with researchers from the computer science department, social science professors and the team of the media centre gave him an overview of the expertise available at the university and contributed to shape his current project focusing on memory.

The brain, memories and generative art

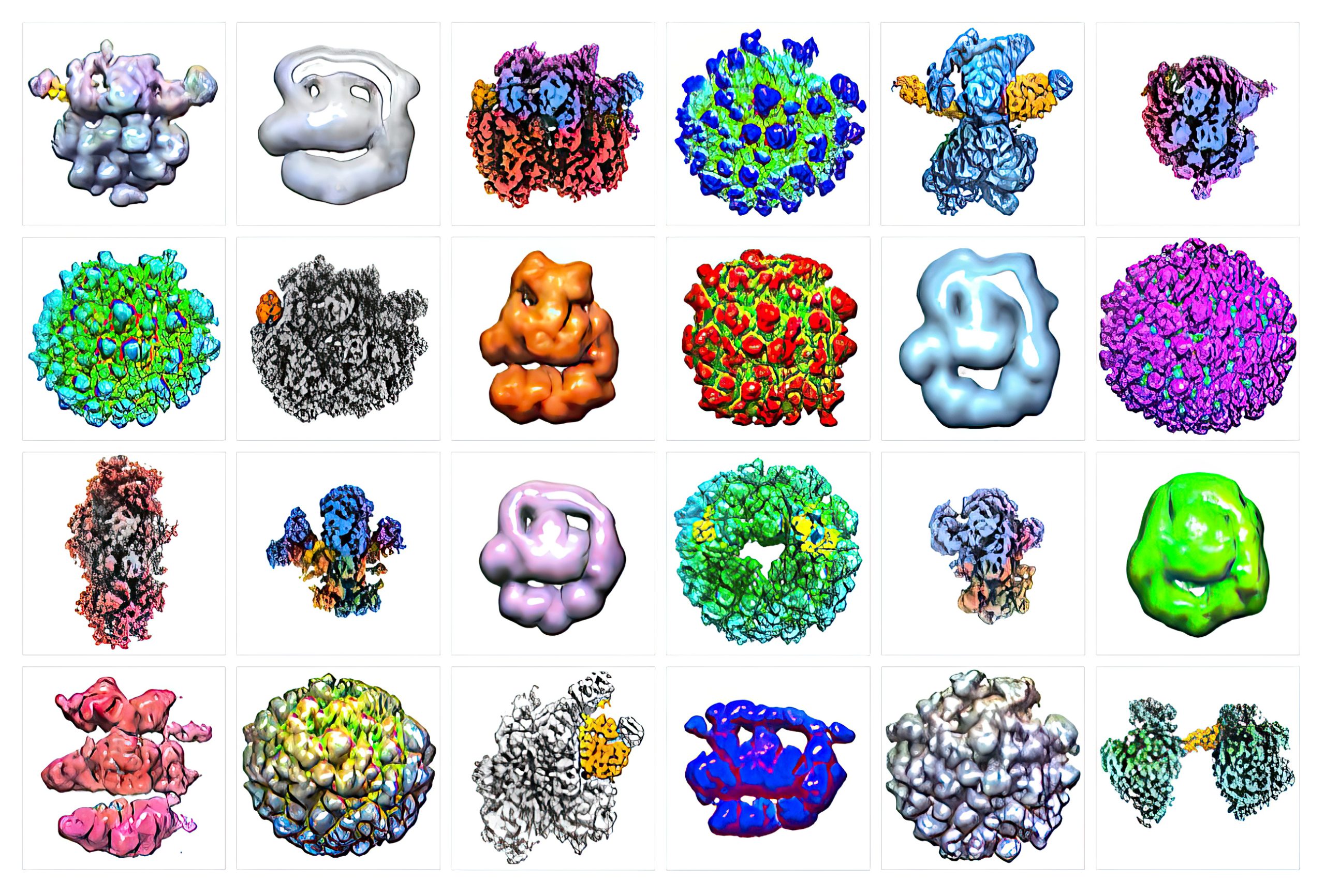

His previous work already had strong connections with natural sciences, from AI-generated images of different classes of animals to 3D structures of speculative proteins that became sculptures, slowly leading up to this project on the plasticity of memory.

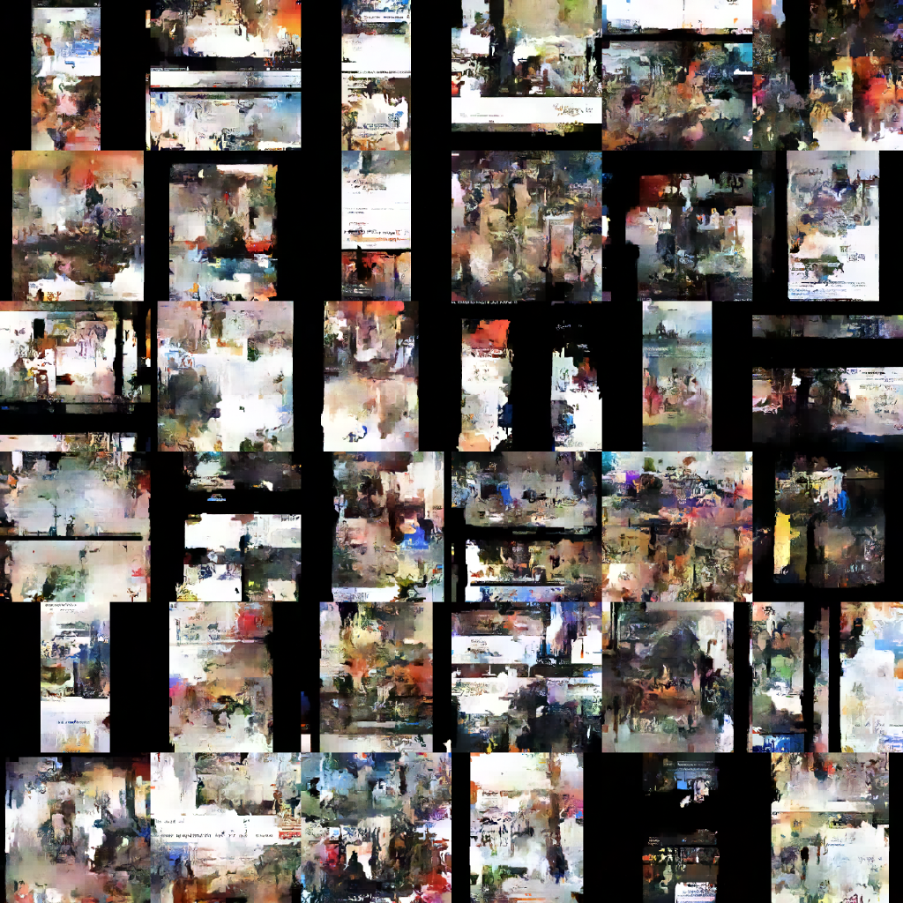

At present, Max Kreis is developing a neural network that, when fed with personal memories, generates fake ones. Trained on all the photos in Max’s cell phone, the model can now not only produce hundreds of new images that resemble dream-like reminiscences from his past but can also create pictures based on a specific prompt and the information available in the database of Max’s photos. In the next steps, the artist will work on refining the model further and will use shape reconstruction to combine the AI-generated fake memories with “ghost shapes” extracted from the same database.

On top of experimenting with this model and the imagery obtained, Max Kreis is also researching how we could reconstruct what our brain sees. In the 19th century, this question already fascinated artists and scientists alike, and some decades later people even claimed to be able to image the soul using X-ray. Nowadays, it is the topic of several scientific projects using the latest imaging technologies. During the two-week residency, Max Kreis and Dr Andreas Husch discussed this question with enthusiastic scepticism: What is the state of the art when it comes to decrypting data from electroencephalograms and functional MRIs? What are the flaws and weaknesses of existing solutions? Is it really possible to reconstruct precise images based on these data? How much scientific truth is there behind big headlines promising new “mind reading” technologies?

Artists and scientists: Common grounds and fruitful differences

This ongoing discussion highlights once more how artistic and scientific processes can be similar, from the curiosity being a driving force to the need for experimentation, trials and errors. “If you think about it, during the Renaissance artists and scientists were often one and the same, Leonardo Da Vinci being the most obvious example,” underlines Max Kreis. “Today, I feel we still question the world in similar ways and we share the same passion for understanding.” Dr Andreas Husch adds: “While modern AI research is deeply grounded in mathematical science, many steps of training artificial neural networks are actually more of an art than a science – based on the experience and intuition of the experimenter to find the right hyperparameters.”

Of course, there are key differences as well: When researchers look for reproducibility and accuracy, artists like Max Kreis have more leeway and can be interested in errors, the outliers in a dataset, the “happy accidents”. As Ben Bausch, doctoral student in the Imaging AI group, points out: “We have different approaches. While we look more at the numbers, Max looks at the visual quality of the result. None of these methods are wrong, they are just different and quite complementary to try to make sense of the world.”

— — —

End-of-residency Symposium

23 October 2024 (14.00 – 18.00)

Casino Display – 1 rue de la Loge – L-1945 Luxembourg