With a diverse background in data and knowledge engineering, plus using digitisation and AI in news archives, PhD candidate Ferdaous Affan aims to shed new light on the historical impact of colonial discourse. She shares more on the challenges of researching propaganda plus the enriching interactions she has had at the C²DH.

The Yves Saint Laurent Museum in Marrakech, Morocco, showcases over 5,000 garments conceived by the French designer, revealing more about his background and how he archived his work—the only haute-couture designer of his generation to do so on a systematic basis.

The museum’s library includes volumes from between the 17th and 20th centuries, related to fashion, gardens and landscaping. It may surprise some that a large portion of the collection is related to Morocco’s colonial past. “There were books on Morocco, mostly written by explorers and colonial administrators, who came during the French colonial era to Morocco,” Ferdaous Affan explains.

The PhD researcher at C²DH served as a library assistant there for one year after earning her degree in Data and Knowledge Engineering from the School of Information Science in Rabat. “While I was working there for a year, I was very much into this catalogue of colonial literature, and it’s one of the links to what I’m doing now,” she explains.

Challenges of propaganda research

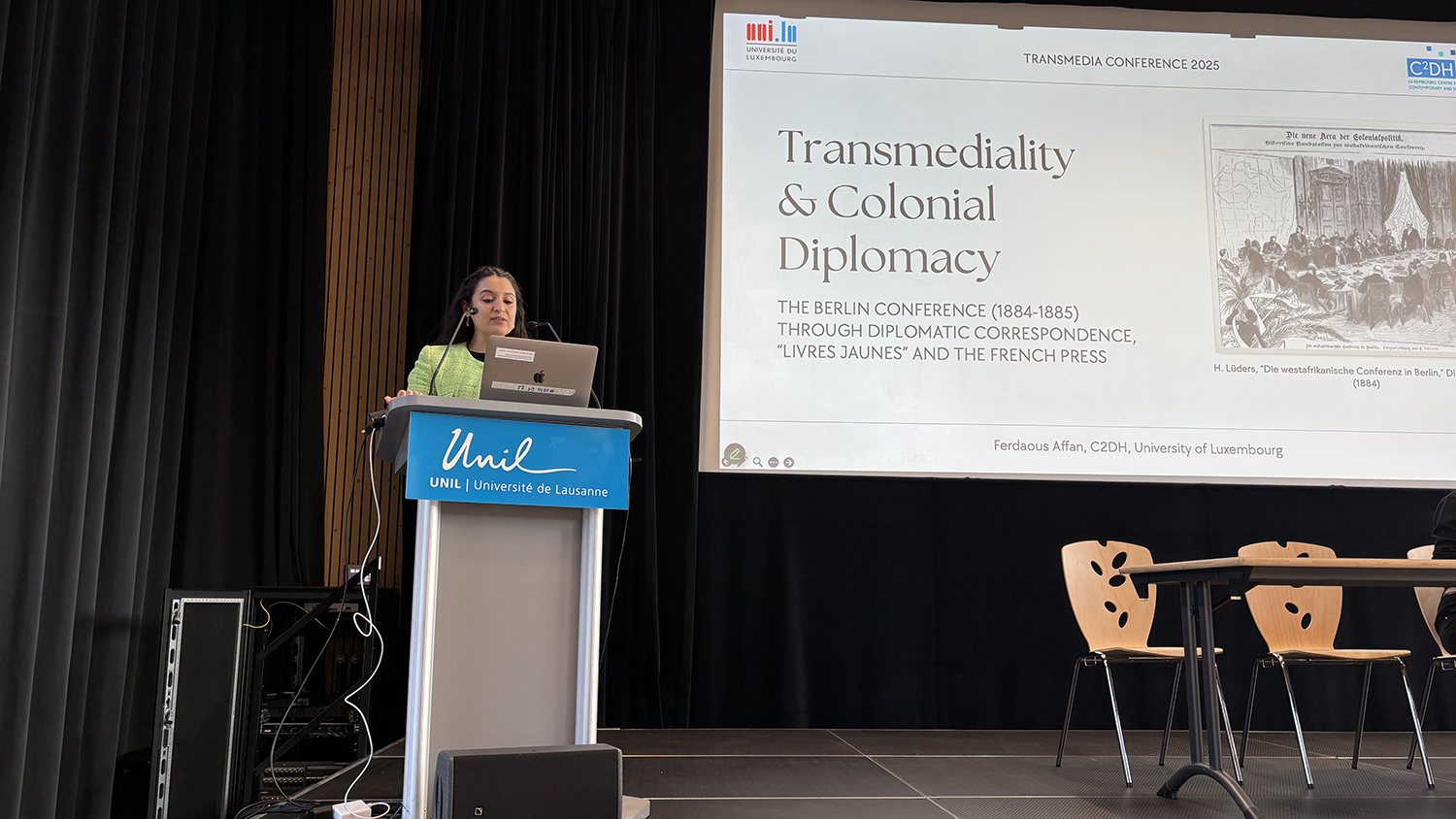

Affan is currently working on her PhD in colonial propaganda in historical newspapers. The full title of her PhD is “Media empire and propaganda: a multi-layered analysis of colonial discourse and power in historical newspapers.”

Her interest in the topic is, in part, a result of her exposure to the colonial works in the aforementioned library. But she also previously worked at the Moroccan News Agency, leading projects involving the digitisation and AI-driven exploration of news archives—a time, she recalls, when tools like ChatGPT hadn’t yet gained traction amongst the broader public.

Through the encouragement of Dr. Marten Düring, Assistant Professor in Digital History at the C²DH, she submitted her application on the topic and believes the fact that it closely aligns to her personal background and interests is what helps make it a good one.

One of the main challenges Affan has faced in her research is defining propaganda. “We have many definitions of propaganda, which are sometimes a bit contradictory to each other, but we don’t have a clear definition of what we mean by ‘colonial propaganda,’” she notes.

‟ We have many definitions of propaganda, which are sometimes a bit contradictory to each other, but we don’t have a clear definition of what we mean by ‘colonial propaganda”

Doctoral researcher

Another layer to this challenge, Affan adds, is that while the concept of “propaganda” as we think of it in current terms has largely been the product of the 20th century, particularly in the aftermath of World Wars I and II, it’s harder to define in the context of the 19th century. Affan’s main source for uncovering colonial propaganda has been historical newspapers published by colonial powers during the Scramble for Africa, and she is often faced with the task of differentiating between colonial propaganda versus what was just considered “normal discourse” at the time the documents were written.

Some newspapers, for instance, published articles describing indigenous populations in Africa in blatantly racist terms, but “there was also this effort by the French government, for the French case, to push colonial policies in the news, and you can see people either encouraging or criticising this—but not really criticising the colonial idea itself,” Affan explains.

Furthermore, many of the articles weren’t signed, and Affan has taken an interest in better understanding who financed those and what the agenda of the publishing houses might have been—and how closely they were aligned with the French government.

One particular case study Affan is investigating is the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, which brought about widespread debate on the future of the African continent. “It was a huge milestone for the Scramble for Africa, and some researchers see it as the starting point for the partitioning of the African continent,” Affan explains. Organised by Otto von Bismarck, the conference brought together 14 countries and laid out the rules of occupation in Africa. Seven of those countries left the conference with formal possessions in the continent.

Not only is Affan researching media coverage around the event, but she is also looking into a particular propaganda tool, namely the livres jaunes (yellow books), diplomatic documents linked to the conference, published by the French government and made public in a bid for transparency. “When I looked into the archives and the correspondences we have now, it’s clear that these were very selective documents, and not everything was made public in these books. It was a selection that would give a good image of French diplomatic actions at this conference,” Affan states.

Eventually, Affan hopes to use network analysis to reveal the flow of information and propaganda between the main actors, which messages were provided through which channels, and to whom those messages were addressed.

Enriching interactions

For Affan, the research hits a bit of a personal note as well. Originally from Tangier, which was an international zone during the colonial era, she says the colonial memory still reverberates, particularly among the older generation. In her research, Affan also plans to include case studies involving the Moroccan Crises of 1905-1911. One of these involves the visit of Kaiser Wilhelm to Tangier in 1905, a moment that heightened tensions between European powers over Morocco’s fate. Such crises underscore the intersection of colonial ambitions, diplomatic manoeuvring and propaganda—dynamics still relevant in contemporary global politics.

Affan’s experience at the C²DH marks her first time living abroad, and she notes that it has been a positive one. She’s able to share her findings and interact with other researchers from very different backgrounds, and she has been impressed with the multilingual nature of the centre and of Luxembourg.

Affan is part of the recently created Deep Data Science of Digital History (D4H) doctoral unit, funded through the FNR’s PRIDE programme, which focuses on the challenges at the intersection between the disciplines of history and data science. “This has been very enriching for me: the interactions I have with colleagues but also those outside the C²DH, who are all working towards the same objective,” Affan says. She is also a contributor to the “impresso – Media Monitoring of the Past II” project, under the supervision of Dr. Düring.